Lost in Transition

Investigation into whether the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services and the Ministry of Health are taking adequate steps to address the inappropriate hospitalization of adults with developmental disabilities

Table of contents

Show

Hide

Investigation into whether the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services and the Ministry of Health are taking adequate steps to address the inappropriate hospitalization of adults with developmental disabilities

Paul Dubé

Ombudsman of Ontario

November 2025

Press conference

Report

Acknowledgement of territory

Ombudsman Ontario acknowledges that the province of Ontario is situated on the lands and territory of more than 130 unique First Nations, each with its own distinct cultures, languages, and histories that predate the existence and boundaries of the province.

We acknowledge the existence of political confederacies on these lands that predate both Canada and Ontario, such as the Three Fires Confederacy and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who among themselves have treaties and relationships that make up the dynamic landscape of this province.

We humbly recognize that we have collective responsibilities and obligations within the more than 40 treaties in Ontario, such as Treaty 3, Treaty 9, the Robinson Superior and Huron Treaties and the Williams Treaties.

We recognize that Indigenous peoples who have cared for these lands for millennia have been dispossessed by colonization, and we seek to find ways to remedy both historic and ongoing wrongs.

We are grateful to have travelled and worked in First Nation territories and with Métis and Inuit peoples in Ontario since the inception of the Ombudsman 50 years ago.

Ombudsman Ontario is committed to building respectful relationships with First Nation, Inuit, and Métis people and communities in Ontario through trust and transparency in order to be able to provide more services for a shared better future.

Contributors

Director, Special Ombudsman Response Team

- Domonie Pierre

Lead Investigator

- Yvonne Heggie

Investigators

- Armita Bahador

- Chris McCague

- Emily Ashizawa

- Emily Dutil

- Richard Francis

- Rosie Dear

- Sonia Tran

Early Resolution Officer

- Rosemary Bowden

General Counsel

- Joanna Bull

- Laura Pettigrew

Counsel

- Ethan Radomski

- Iris Graham

Executive Summary

1 In an article published in 1960, journalist and author Pierre Berton described his disturbing findings during a visit to the Huronia Regional Centre in Orillia. The piece was a clarion call for reform of Ontario’s system of institutionalized care for people with developmental disabilities. It ended with the chilling words: “Do not say that you did not know what it was like behind those plaster walls, or underneath those peeling wooden ceilings.”

2 In the decades that followed, society responded with a commitment to deinstitutionalization, recognizing the inherent dignity and rights of people with developmental disabilities. Governments pledged to close institutions and replace them with community-based supports, to allow individuals to live with autonomy and dignity.

3 However, while institutions like Huronia have closed, the reality of fulfilling this promise has been complex. Gaps in suitable housing and services have left many without the support they need, leading to a modern form of institutionalization by default. Today, though we no longer intentionally consign people with developmental disabilities to institutional settings, an overburdened and under-resourced system has resulted in some – particularly those with complex needs – being placed in hospitals or other inappropriate settings due to a lack of viable alternatives.

4 In August 2016, I released Nowhere to Turn, my report on the results of my Office’s investigation into the response by the Ministry of Community and Social Services (as it was then called) to cases of adults with developmental disabilities in crisis situations. I observed that because of limited community supports and services, “with nowhere else to turn, those in crisis can find themselves inappropriately housed in a variety of institutional settings from hospitals to jails.”

5 I issued 60 recommendations to the Ministry to address systemic challenges in the developmental services sector. Five of my recommendations specifically focused on the default institutionalization of adults with developmental disabilities in Ontario’s general hospitals and psychiatric facilities.

6 We closely followed the Ministry’s progress in implementing my recommendations, as we continued to receive complaints. Some system improvements occurred over time, but we continued to hear from family members and concerned professionals about the inappropriate and sometimes years-long hospitalization of adults with developmental disabilities. We heard that hospitals frequently managed some individuals by applying chemical and physical restraints, and that the condition of many deteriorated during their long stays in hospitals.

7 When people with developmental disabilities languish in hospital, systemic challenges in the health care and developmental services sectors intersect. By March 2023, I decided to launch a new investigation focused on what is now called the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (the MCCSS), as well as the Ministry of Health (the MOH), to determine whether they were taking adequate steps to ensure that such individuals can transition to appropriate homes and supports in the community.

8 This report features the stories of seven people[1] experiencing prolonged and unnecessary hospitalization – waiting months and even years for suitable living and support options:

- Jordan, 25, was in hospital for 15 months, scared and sometimes restrained in a noisy and unpredictable environment.

- Jack, 57, lived in hospital for more than eight years, only to finally move to a home three months before his death.

- Luc, 30, a Franco-Ontarian, was hospitalized for more than four years, often without access to care and services in French, and was regularly subjected to mechanical and chemical restraints. He moved to the community briefly, but returned to hospital, where he remains to this day.

- Noah, 22, was tied to his bed and chemically sedated for most of his more than two years in hospital.

- Sean, 27, lived in a forensic psychiatric hospital for five years, physically restrained at times for up to 20 hours a day, before he transitioned to a supportive living home.

- Kevin, 27, was in hospital, sometimes restrained or isolated, for more than two years before he moved to a community home.

- Anne, 59, desperately wanted out of hospital, but wasn’t able to leave for more than two years.

9 All of them suffered some form of regression, loss of previous life skills, or deterioration in their physical and mental functioning during their time in hospital. Their declining conditions further compromised their ability to find a community home and a willing service agency capable of meeting their needs.

10 As Ombudsman, I have a responsibility to bring “the lamp of scrutiny to otherwise dark places, even over the resistance of those who would draw the blinds.”[2] In this report, as Pierre Berton did in his own way 65 years ago, I have opened the blinds and revealed glimpses into the lives of seven particularly vulnerable people whose personal dignity, integrity, freedom, and quality of life were compromised in an institutional environment that was never designed to meet their needs.

11 Unfortunately, their stories are not unique. They are representative of a broader problem, as evidenced by the multiple complaints we have received about people in similar situations. We know that there are others in Ontario who remain confined to hospital beds, waiting for a home in the community. There is no comprehensive accurate count of the number of people with developmental disabilities inappropriately living in Ontario’s hospitals, the number of people waiting for supportive living, average wait times for that housing, or the number who are served each year. The figures that are available are inconsistent and not generally available to the public. MCCSS documents show there are close to 30,000 Ontarians with disabilities registered for Ministry-funded supportive living. Ministry of Health records suggest that dozens may be waiting in hospital to transition to homes in the community, but the available data from an October 2024 study by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health[3] suggest that the number may actually be in the hundreds.

12 I am making 24 recommendations to improve the availability and transparency of supports and services to people with developmental disabilities and complex care needs. I am calling on both ministries to bridge the divide between the health and developmental services sectors, work jointly towards integrated solutions, and undertake proactive system planning to reduce inappropriate hospitalizations in future.

13 This investigation has also confirmed that important recommendations from my 2016 report, Nowhere to Turn, remain unfulfilled. I am hopeful that this new report will serve as a catalyst for both ministries to unite to work toward resolving these systemic issues. I will monitor their progress closely.

Investigation Process

14 This investigation focused on the experiences of individuals with developmental disabilities who remained hospitalized for extended periods while awaiting appropriate housing and support services that would enable them to live safely in the community. We explored the barriers that prevent timely transitions out of hospital, as well as the steps being taken by relevant ministries to address these issues.

15 Between April 2020 and the March 27, 2023 launch of this investigation, we received 15 complaints about individuals with developmental disabilities languishing in hospitals, sometimes for years, with no end in sight. Since the launch of this investigation, we received more than 40 additional complaints about people in similarly difficult situations. In this report, we highlight seven representative cases that illustrate the complex challenges and human struggles they face.

16 Over the course of this investigation, we interviewed more than 120 people, including hospitalized individuals, their family members, hospital and clinical staff, service agencies, Developmental Services Ontario staff, and representatives from community and advocacy organizations. We also spoke with frontline and senior officials from the Ministries of Health and Children, Community and Social Services, as well as Ontario Health. In addition, we reviewed thousands of documents from the ministries and interviewees, and conducted supplementary research.

17 We continue to review individual complaints and make inquiries with government officials, working to resolve the issues wherever possible. Unfortunately, this often proves difficult because of the systemic barriers described in this report.

Legislation Overview

18 For more than a century, Ontario operated segregated institutions to house people with developmental disabilities.[4], [5] During the 1970s, the model for delivering these services began to transition from medical and institutional to community-based programming. In 1974, the Developmental Services Act[6] became law and established a framework for the creation, funding, and operation of community services for those with developmental disabilities. The responsibility for operating Ontario’s 16 institutions also shifted from the Ministry of Health to the Ministry of Community and Social Services. In 1977, the province launched a plan to increase community supports and decrease reliance on institutional care.

19 Today, the Services and Supports to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008[7] governs the provision of these services and supports in Ontario. The Act was intended to modernize developmental services, enable more independence and choice, and support transition to a community-based model and greater social inclusion. It also aimed to increase fairness and uniformity in eligibility, assessment and access to services, and to simplify the process for accessing supports, services, and funding.

20 The Act provides for “application entities” to act as a single point of access for services and supports within each geographic region of the province. It also contemplates the creation of “funding entities.” However, the provisions for creating funding entities have never come into force.

21 In 2021, the government published an aspirational vision for long-term developmental services reform, called Journey to Belonging: Choice and Inclusion.[8] The document envisions a future where communities, support networks, and government will support individuals with developmental disabilities to be “empowered to make choices and live as independently as possible through services that are person-directed, equitable and sustainable.” The Journey to Belonging vision also emphasizes proactive planning and integrating supports with other sectors.

Developmental Services and Health Care

22 Adults with developmental disabilities may be admitted to hospital for medical reasons. After their acute medical issues are resolved, some remain because their families or service agencies can no longer care for them in the community. Others do not require medical care, but arrive at hospitals because there is simply nowhere else that can provide the services and supports they require.

23 In some cases, hospitals designate these individuals as “alternate level of care” patients – a term for someone who is occupying a hospital bed even though they do not require acute hospital care. Other “long stay” patients with developmental disabilities are not formally classified as alternate level of care but remain in hospital only because there is no appropriate supportive living accommodation for them in the community. As I noted in Nowhere to Turn, the hospital sector has a longstanding concern about such patients diverting finite medical resources.[9]

24 Adults with developmental disabilities who spend prolonged periods in hospital are involved with two distinct systems: Developmental services and health care.

25 I refer to these clusters of programs and services as “systems” throughout this report. However, they do not necessarily display the interconnected, strategically planned, and organized structure typically characterizing “systems” when it comes to addressing the needs of individuals with developmental disabilities. Some programs and services are ad hoc, reactive, and vary by location. The level of coordination and communication between developmental services and health care services varies when it comes to supporting individuals with developmental disabilities in transitioning to the community.

System overview

26 When someone with a developmental disability remains in hospital because there is no suitable community option, there is a labyrinth of developmental services and health agencies and processes that may be involved to help connect them to needed supports and housing. Collaboration between these entities, along with adequate funding, is usually necessary to establish a suitable transition plan out of hospital.

27 The Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (MCCSS) and the Ministry of Health (MOH) each have some responsibility in supporting people with developmental disabilities, but they operate from the perspective of their differing mandates. The MCCSS plans, funds, and oversees the developmental services sector, while the MOH stewards the effective management of health services, including hospitals. Part of the MOH’s role includes ensuring that individuals can access “the right care in the right place.”[10]

28 Adults seeking MCCSS-funded developmental services must apply, be deemed eligible for, and be registered with Developmental Services Ontario (DSO), which is the access point for funded supports and housing. Nine regional DSO offices review applications and eligibility for MCCSS funded services within their regions. DSO offices refer eligible individuals to available services and maintain registries for requested services, such as supportive living accommodation, community participation, and short-term respite relief. MCCSS-funded supportive living options within developmental services include group homes, host family homes, supported independent living, intensive support homes, and specialized accommodation. The level of support, including staffing levels, varies depending on the type of home. Intensive support homes and specialized accommodation generally provide 24-hour staffing support and may have access to clinical supports for those with complex needs or a dual diagnosis (having both a developmental disability and mental health diagnosis).

29 Once registered with DSO, there are often long waits for ministry-funded services and supportive living spaces because the demand far exceeds supply. For this reason, DSO uses an algorithm to prioritize access to funded services based on an individual’s level of risk of adverse outcomes, including risk of homelessness. If someone is deteriorating in hospital or at risk of discharge with nowhere to go, this can affect prioritization for service. Therefore, it is important that their hospitalization is communicated to DSO. DSO may also be able to refer an individual with complex or multiple needs to a case manager or to developmental or behavioural services, to help them while in hospital. Such supports are often critical to facilitating communication between individuals (some of whom may be non-verbal) and hospital staff. They can also help mitigate loss of skills and develop transition plans.

30 If there are no funded services or housing options available to meet a person’s needs, as is often the case, DSO may refer their case to a community planning table. Table participants include MCCSS-funded service agencies and sometimes MCCSS representatives, and potentially other sector partners, such as health professionals.

31 Service agencies at the planning table review urgent and priority cases to see if they have appropriate and available resources, including supportive living space or other supports. Agencies have discretion on whether or not to support an individual. They may do so on their own or in collaboration with other agencies and services. For those who have high support and complex care needs, the Community Network of Specialized Care may work with individuals, agencies and planning tables to help coordinate support across service systems, including developmental and health systems.

32 Even if a supportive living space is available, additional funding is often needed to pay for physical modifications and other supports that enable individuals with developmental disabilities to live safely and successfully in the community. Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP)[11] funding or Passport funding[12] that individuals with developmental disabilities may be eligible for is not intended for purchasing or renovating housing and is often insufficient to cover the costs of hiring direct support staff for those who need full-time support and higher support ratios. These costs can run into hundreds of thousands of dollars or even more than $1 million per year for those with particularly high needs.

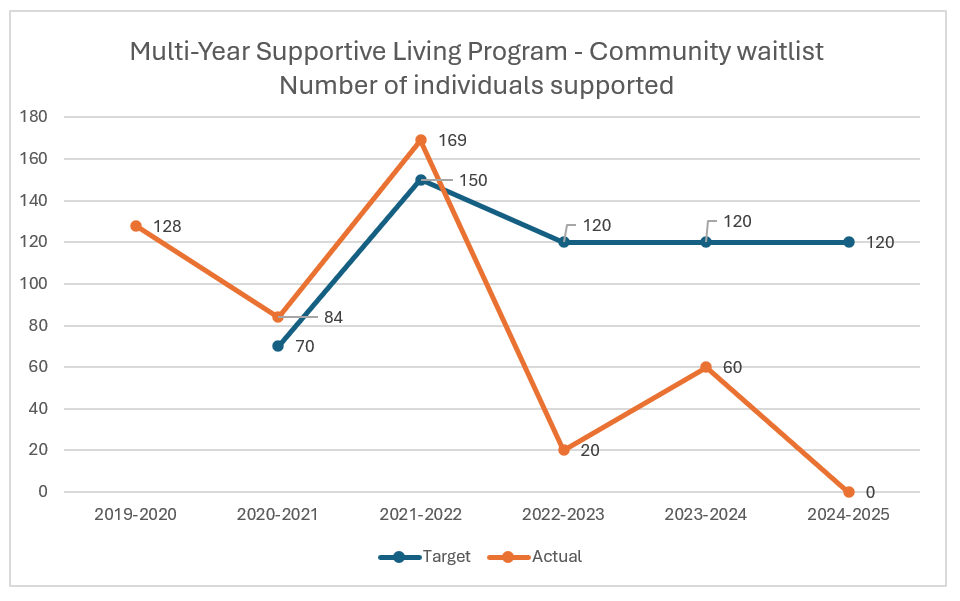

33 The MCCSS provides limited funding to build additional capacity in developmental services. Through the Multi-Year Supportive Living program, funding may be allotted annually to support certain prioritized individuals within each region. The funding often helps people who are in inappropriate settings, such as hospitals or shelters, to pay for needed housing and other required services so they can live safely within the community.

34 In addition to the Multi-Year Supportive Living program funding, from 2021 to 2023, the MCCSS and MOH jointly funded a project to help individuals with a dual diagnosis transition out of hospital. Called the Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project, it involved collaboration between the ministries, Ontario Health, and MCCSS regional offices. The funding was limited and depended on individuals being identified for consideration and highly prioritized for service. It was also restricted to those with a developmental disability and formally diagnosed mental health disorder (dual diagnosis).

35 In some cases, hospital social workers or a case manager can help connect a person to a private supportive housing option if the individual can afford it or can access government funding to cover the costs. Others may consider an MOH-funded supportive living home if there is one available that meets their needs, though these homes often have long wait times or are not suited to people with developmental disabilities and complex needs.

36 Some individuals may also require clinical supports to transition from hospital to the community, such as psychiatric or nursing supports. Others may need specialized treatment, such as through a hospital-based dual diagnosis program to address behavioural challenges on a time-limited basis. Case managers, complex case coordinators, or hospital staff may be involved to help individuals or service agencies access these services.

37 Ontario Health is a Crown Agency that aims to “connect, coordinate, and modernize” the healthcare system.[13] Its objectives include promoting “health service integration to enable appropriate, coordinated and effective health service delivery”.[14] Ontario Health explained that, as part of this role, they oversee the management of all populations in hospital who require an alternate level of care, which can include individuals with developmental disabilities. Hospitals are responsible for reporting alternate level of care patients to Ontario Health, as the number of hospital beds occupied by people who no longer require hospital care affects access to timely health care for others waiting for a bed. Among the things hospitals can report to Ontario Health is whether someone in an alternate level of care bed has “developmental requirements”[15] that are preventing discharge. Unfortunately, as our investigation found, the numbers are not always reliable.

Suspended Lives: Stories from Hospital Beds

38 The stories of the seven people highlighted in this report illustrate the hardships often faced by adults with developmental disabilities, particularly those with complex needs, when they find themselves stranded in hospitals with nowhere to go.

39 The cases we document include periods of hospitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic. While in some cases the pandemic exacerbated conditions that prevented timely transition out of hospital, it does not fully explain the delays. The systemic barriers that lead to inappropriate hospitalizations and the inability to access suitable services and supportive living existed long before the pandemic and persisted after its end.

40 These seven individuals are not alone. We continue to hear from concerned families and professionals about others in similar situations. As of December 2024, Ontario Health reported that there were 124 adults with developmental disabilities residing in hospitals who no longer required acute medical care. The list is not complete. Hospitals do not always recognize and report that a patient has a developmental disability, and there are various reasons why a hospital might not designate someone as alternate level of care, even though they remain in hospital only because there is no suitable alternative.

41 The stories that follow detail how seven particularly vulnerable members of our society needlessly languished in hospitals, interminably waiting to find a place in their communities. No matter how compassionate and caring staff within a hospital may be, a hospital is not a home.

Catch-22: Jordan’s story

42 Jordan, a 25-year-old who enjoys spending time with his family, spent 15 months in hospital waiting for an appropriate home in the community. He has autism, cerebral palsy, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, and conditions that affect his heart and liver. Jordan is non-verbal and uses a tablet to help him communicate. He also requires help with daily tasks like using the toilet, bathing, and brushing his teeth. Although he had been a happy young man, Jordan’s behaviour deteriorated during the COVID-19 pandemic. He became so aggressive and violent, it was not safe for him to remain at home.

43 As the outbursts escalated at home, Jordan’s mother could no longer work. She told us she grew so hopeless, she thought at one point that the only way to give her husband and other son their lives back might be to kill Jordan and herself. Without sufficient support, she felt “there was no solution...there was no help. There was no end in sight.” When Jordan tried to strangle his aunt while his mom ran an errand, the family was forced to call 911 for help and Jordan was admitted to hospital.

44 In the hospital’s psychiatric intensive care unit, Jordan was scared and often aggravated by the screaming of other patients in crisis. When first admitted, Jordan did not have access to developmental support staff and, without consistent access to his tablet, his parents said he struggled to communicate with hospital staff about his basic needs. At times, he was left to lie in urine-soaked sheets.

45 The hospital told us that staffing ratios did not allow for Jordan to receive the level of care he needed. They also agreed that the psychiatric intensive care unit was an extremely challenging environment for individuals like Jordan on the autism spectrum. There are no routines, and nursing staff frequently change and are not typically trained to communicate with someone with autism. Ill-equipped to deal with his behaviour, hospital staff initially physically or chemically restrained Jordan, sedating him or tying him to the bed. Jordan’s parents said that at times, they needed to be at the hospital up to 12 hours a day to help meet his care needs.

46 Jordan’s mother said they felt trapped in a “never-ending sort of loop.” She said service agencies seemed unwilling to work with Jordan because he was “too violent,” while private treatment programs that could potentially help to address aggressive behaviours turned him down because he would not have a place to live when the program ended. Jordan was in a classic Catch-22 situation: Without treatment, he could not get housing, and without housing, he could not get treatment.

47 Even though Jordan was a high priority for developmental services, no housing vacancies met his needs and there was insufficient Ministry funding for the 2:1 staffing ratio he required. A space for Jordan in the community only opened up when a resident died and Jordan was selected to receive funding through the Ministries’ joint Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project. He finally moved into his new home on November 7, 2023 – 15 months after he was first admitted to hospital. Jordan is now doing “fantastically” in his home and sees his parents and brother regularly.

“Get me out of here”: Jack’s story

48 Jack grew up in the community with his family and loved everything to do with cars. He was diagnosed with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, had trouble in school, and never learned to read. However, for five decades, no one identified him as a person with a developmental disability, and he never received associated supports or services.

49 Jack lived in a series of unsuitable housing arrangements throughout his adult life. When not monitored closely, he would drink so much fluid that he would at times have seizures that resulted in hospitalizations. Eventually, unable to care for himself in the community, and with nowhere else to go, Jack ended up spending more than eight years in hospital. He told us he didn’t belong in the hospital and felt like no one was helping him.

50 He also expressed frustration with having no control over his daily activities, including such basic things as when to have a shower. He was concerned about other patients entering his room, and hospital staff said he was assaulted several times by other patients. Hospital staff likened Jack’s living situation during COVID-19 to being in “a jail,” with no access to family or the outdoors beyond the courtyard. During that time, hospital staff said Jack told them he felt like he “didn’t belong anywhere.” They said he pleaded with his mother to “get me out of here.”

51 Only with the support of a persistent and caring hospital staff member was Jack’s developmental disability formally diagnosed. In 2020, he applied for and was deemed eligible for developmental services. It still took another 3.5 years to find a home and suitable funding for him to live outside hospital, as he required 24-hour supervision and a custom-built living space to allow him to live safely.

52 Jack was initially overlooked for the joint Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project funding even though he had a dual diagnosis, had been in hospital for years, and was designated alternate level of care. He was only added to the list after our Office made inquiries about his case. Ministry staff said he was likely overlooked because he was in a cognitive care bed in hospital rather than a mental health bed. Eventually, when a resident of a local MCCSS-funded home died and Jack was granted project funding, he was finally able to leave hospital. Tragically, Jack only enjoyed his freedom for three months before he died. He was 57.

Losing hope: Luc's story

53 Luc, 30, is a Francophone who loves computers and is described as a “nice guy.” He lives with severe autism, an intellectual delay, seizure disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Luc also has a condition that causes him to compulsively and repeatedly pull off his own nails and pick his skin to the point of injury.

54 Even with intensive supports in place, Luc feels compelled to destroy things around him if he sees an imperfection or something that doesn’t match. In a persistent state of crisis and burnout, his family wrote to the MCCSS in February 2020 to seek more help, explaining that the situation at home had become “dangerous.” Sadly, a few days after writing this letter, Luc's family had to call 911 after Luc lost control, started pulling out his fingernails, and head-butted his father in the family car. Luc was admitted to a hospital’s psychiatric unit and, apart from a brief move to a home in 2024, has remained there for close to five years.

55 The hospital’s loud and often tense environment is challenging for Luc. He is confined to his hospital room for long periods. When he becomes agitated, hospital staff use physical restraints or administer medication to sedate him, as they do not have the staff ratios to provide the support he requires. At times, French-speaking hospital staff are not available, which his family and others say results in Luc feeling misunderstood, further contributing to frustration, escalation, and the use of restraints.

56 Extraordinary efforts were taken to connect Luc to supports in the hospital and to find appropriate housing and support for him in the community. A Francophone agency started planning for Luc to transition out of hospital, but this fell through when they realized that Luc’s needs exceeded the support they could provide. Ministry officials worked with a case manager to assess all potential French-language options in the Region. When that proved fruitless, they expanded the search to English-speaking agencies who could provide bilingual services, and even looked out of province. However, service agencies either lacked the staffing and resources Luc required or were reluctant to support someone who had only lived at home or in the hospital when pandemic related visitor restrictions prevented them from meeting with him in person to assess current skills and behaviours. During the search, regional staff documented that “[t]here is a clear lack of current capacity to provide high support residential care in the… area to individuals with extraordinary behaviour needs….”

57 Finally, after more than four years in hospital, an agency agreed to transition Luc to the community, but his respite was short-lived. After only six months, the agency could no longer manage his behaviours. Despite 3:1 staffing, psychiatric support, and the services of a behavioural therapist, several staff were injured. Luc was again admitted to hospital, and shortly thereafter, the agency providing behavioural support withdrew its services. He was essentially back to square one. After several months in hospital, another service agency offered to potentially develop a support plan to enable Luc to transition out of hospital. These efforts are ongoing, but, in the meantime, the family is again concerned that he is being restrained in his hospital bed for long periods, rarely able to leave the psychiatric unit, and losing hope.

“Quite inhumane”: Noah’s story

58 At 22, Noah is described as “full of life” and enjoys listening to music and going for walks. He is on the autism spectrum, non-verbal, suffers from anxiety and seizures, and functions developmentally as a 12-18-month-old. Raised at home by his mother, Noah never attended school and had limited involvement with developmental services. As he got older, Noah’s behaviour became increasingly aggressive and difficult to manage. His mom repeatedly feared for his and her own safety and either brought Noah to hospital or called emergency services. After a series of hospital admissions and discharges, Noah was admitted to hospital in August 2021 and remained there for almost two and half years.

59 In his first few months of hospitalization, those supporting him said that he was relatively “restraint free.” However, by his eighth month in hospital, his self-injurious and aggressive behaviours were escalating. Noah was tethered to his bed through all of his waking hours, in a spreadeagle position using either three or four-point restraints. Hospital staff also regularly chemically restrained him with sedating medication. Those close to Noah told us that he went from being able to toilet, bathe, and dress with limited help to using a diaper, needing assistance to walk, and losing his basic life skills. When staff were unavailable to take him to the washroom or change his diaper, Noah lay in his own urine-soaked bed sheets, sometimes for hours.

60 During his last year in hospital, Noah’s diapers became so saturated that they would form chunks, which Noah began to pick at and eat the pieces. A professional working with Noah documented that he spent “no longer than 60-120 minutes per day out of restraints.” Noah’s mother told us he would bang his head on his bed while he was tied down – and twice injured himself to the point of bleeding. He also frequently kicked the wall and injured a toe so severely that it had to be amputated.

61 A professional supporting Noah who observed him in hospital remarked, “You feel completely like...you’re witnessing almost...a profound level of neglect that you can’t do anything about…” Another said that this was “the worst case I’ve ever been involved in and ...it has a profound impact on the people that support him...I would like to know if there’s anybody in Canada who’s being treated as poorly….”

62 The extensive use of restraints, we were told, largely frustrated efforts to assist Noah. One clinician explained that they were unable to get Noah to a “community-ready state” in a hospital environment under these conditions. By summer 2022, DSO classified his needs as having increased to the maximum level. DSO staff said they had never seen this before and it was likely due to the extended use of restraints, increased aggressive behaviours, seizures, and mobility issues acquired during his stay in hospital.

63 Despite being near the top of the priority list for developmental services, it proved difficult to find suitable housing and support for Noah in the community. His profile was considered through the local planning table’s urgent response process, and added to registries outside his immediate area, but no service agency initially came forward to help him. In an effort to encourage agencies to step forward, Noah’s case manager updated his service profile to better reflect his personality and interests before he entered the hospital. She also emailed the Ministry, saying “things are getting quite inhumane” in hospital, and asking to meet to discuss a plan for Noah.

64 Finally, in December 2022, after MCCSS regional staff organized a meeting bringing together the case manager, Ministry-funded service agencies, and the Community Network of Specialized Care, a service agency came forward and began to plan for Noah to transition to the community. After months of searching, the agency located a single-family home it could rent for Noah – if it received sufficient capital funding to make the space suitable for his needs and additional funding for 2:1 staffing support. The agency confirmed Noah met the criteria for Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project funding and, in October 2023, the Ministry approved an annual budget for him. In March 2024, he moved into his new home. Service agency staff now support Noah in the home, with local hospitals providing needed psychiatric and behavioural therapy. After two years largely confined to his hospital bed, Noah now wears his own clothes, no longer requires a diaper, and can even play soccer in his yard.

Unfit to stand trial: Sean’s story

65 Sean enjoys playing basketball, video games and listening to music. He is 27, but functions at approximately the cognitive age of a 5-year-old. He has been diagnosed with autism and chronic adjustment disorder, and lives with a stoma as a result of a Crohn’s disease-related colostomy surgery he had as a teenager.

66 Sean has aggressive behaviours and can become violent. By January 2019, his family was frequently calling police for help. One record we reviewed noted the family had called emergency services 28 times in the span of eight months; another documented more than 20 short-term visits to six different hospitals within seven months. Psychiatric specialists consulted on Sean’s case recommended more community-based supports and behavioural interventions. They observed that hospital environments exacerbated Sean’s behaviours and recommended solutions outside of hospital settings.

67 At home, the family continued in a state of crisis. Recognizing that the situation was not sustainable, service agencies made efforts to connect Sean to additional support and added him to a waitlist for a specialized treatment bed to provide short-term intensive treatment to help stabilize his behaviours. They wrote that without a safe and secure housing option with access to behavioural supports for Sean, “an extremely unsafe, untenable and dangerous situation and harm” would continue.

68 Unfortunately, no option was found, and Sean attacked his mother at home in December 2019. This time police suggested he be charged criminally to compel necessary supports through the justice system. After police laid charges, the court issued a no-contact order preventing Sean from returning home, and he was admitted to hospital under the Mental Health Act. The court later found Sean “unfit to stand trial” and remanded him to a psychiatric treatment hospital. The Ontario Review Board ordered that he remain there until housing with 24-hour supervision in the community could be located.

69 However, with no appropriate housing and services available to meet his needs, Sean remained at the psychiatric hospital for more than five years.

70 To manage Sean’s aggressive behaviour and self-harm, the hospital relied on mechanical restraints at various points during his hospitalization, at times up to 16-20 hours a day. Developmental sector staff supporting Sean observed that the transition from living with his family to a secluded hospital setting was scary for Sean, and behaviours were exacerbated by the frequent staff turnover because he does not do well with change and struggles with new people. While Sean had previously been able to participate in the care for his stoma, his self-injurious and aggressive behaviours increased in hospital and the process now took six staff to complete.

71 Efforts to find Sean a home were further complicated by his aggressive behaviours and complex medical needs and, at times, he was not medically cleared for discharge. His needs increased because of the time spent in hospital, which meant he would require a higher staffing ratio in the community than he would have before his hospital stay, at a much higher cost. A rural location was initially considered but ruled out primarily because of the distance from medical supports, the complexity of transporting Sean long distances to receive care, and the service agency’s inability to recruit sufficient staff in the area.

72 Finally, when a supportive living vacancy located in a city arose, the service agency supporting Sean was able to renovate that space and arrange necessary staffing and supports with sufficient Ministry funding and access to nursing and psychiatric support. Since moving into the home, Sean is now able to go outside, celebrate holidays, and live more independently. A sign Sean made for his entryway reads, “This is my forever home.”

Worse than prison: Kevin’s story

73 Kevin, 27, loves listening to music. He has autism, is largely non-verbal, and lashes out aggressively when he’s frustrated. His mother told us she felt unsafe every day when Kevin lived at home with the family. She worried about Kevin’s younger brother, who would hide in his room to feel safe. Kevin was registered in a day program and the family was able to obtain some services with Passport funding but, when his supports fell away due to the pandemic and other issues, the situation at home escalated.

74 The family was registered for supportive living through DSO but were told it could take years to access housing, even though Kevin was a priority in the community.

75 Kevin’s parents struggled to manage his behaviours at home. Police were called on multiple occasions in response to his violent behaviour, which would lead to him being taken to hospital and then discharged. At one point, Kevin bit his father’s finger so badly that it required surgery. In November 2020, after another episode of aggression, police were called, and Kevin was brought to hospital and ultimately admitted to the psychiatric unit.

76 His mother described the hospital setting as “worse than prison.” To manage his behaviour, Kevin was monitored by security guards, sometimes restrained or isolated, and had few opportunities to leave his small unit. Hospital staff acknowledged that the psychiatric unit was not the best environment for Kevin. His physical and mental health declined, and he seldom smiled like he used to. Despite the hospital being “desperate to discharge” him and local planning tables identifying him as “one of the highest need [individuals] for high behavior [supportive living],” it took more than two years to transition Kevin to a home outside hospital.

77 Initially, there were no suitable vacancies for Kevin and the Ministry did not know what, if any, funding would be available to support him.

78 When he was diagnosed with a mental health condition after a year in hospital, he was one of a select few individuals who qualified for Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project funding. However, he still had to wait months for another resident to move out of existing housing before an appropriate spot opened for him. Kevin finally moved into a home with a yard in January 2023.

“I just give up”: Anne’s story

79 Anne loves knitting, swimming and animals. She has autism, generalized anxiety disorder, a mild developmental delay, and struggles with obesity. She is 59, but wasn’t connected to developmental services until she was over 50 – and has experienced several living arrangements that broke down or did not meet her needs.

80 While living in a supported independent living home that did not provide the level of support she required, Anne was intermittently admitted and discharged from hospital. Finally, desperate for a change and believing that someone would come and get her, Anne left her supported independent living home to go to a hotel. She was found by hotel staff three days later, alone and unable to get up, lying on a soiled bed with nothing to drink and only dry cereal to eat. They called an ambulance.

81 Anne was re-admitted to hospital in late December 2020 and, a few months later, transferred to a specialized dual diagnosis program in another hospital. She returned to the local hospital in May 2022 and remained there for two and a half years. Anne told us that she spent most of her time in hospital in bed, and she wanted to live on her own in the community where she could have friends. She said she felt stuck and said of the lengthy hospital stay, “I just give up because... I’m not happy.”

82 Hospital staff, DSO, and a complex case manager with the Community Network of Specialized Care all worked to find housing options for Anne, but she was passed over for seven funded spaces because her needs “didn’t quite match.” Ministry staff said they believed Anne’s mental health needs, along with a lack of funding, were a barrier to finding a suitable home. After more than two years in hospital, Anne was not considered for Multi-Year Supportive Living funding and was overlooked for Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care funding – until our Office made inquiries into her case. Hospital staff who were trying to help her find a home expressed frustration and concern about how Anne was being treated. They noted that it was neither patient-centred nor an appropriate allocation of resources, given that she was in a publicly funded acute care bed.

83 Two options with private service agencies arose while Anne was hospitalized, but they fell through. Even though Anne had been rejected for several Ministry-funded housing options, the Ministry told us that private agencies are only considered as a last resort, and there was just no funding available. Anne was also added to the waitlist for a MOH supportive living home, but after a year had only moved from 11th to eighth position on the list.

84 Finally, Anne was able to move into a private retirement home for seniors after a service agency involved in her case agreed to pay the upfront costs from its operating budget, with Ministry reimbursement in the new fiscal year. Despite the financial hardship it faced, the service agency agreed, just to help get Anne out of hospital. Three days after the transition, the agency told us she was doing remarkably well, and they were seeing the “best version” of her. After four months living in the retirement home, her case manager said Anne was continuing to do well, was regularly eating with other residents in the dining room and had been able to visit with her previously estranged daughter.

High Demand, Short Supply: Barriers to Transition

85 The primary reason for prolonged hospital stays is the chronic shortage of suitable supportive living accommodations in Ontario. There was no acute medical need for the seven people featured in this report to remain in hospital, but there was nowhere for them to live safely in the community.

86 For years, the demand for supportive living accommodations in the developmental services sector has far outstripped supply. Between 2020 and 2024, the number of people registered with DSO who were waiting for supportive living increased from almost 24,000 to 28,500.

87 An internal briefing note to the Minister of Children, Community and Social Services in April 2023 noted that this number had grown at an average rate of 9% per year over the previous four years, with “essentially” no increases in the number of people served.[16] Indeed, the provincial Financial Accountability Office’s 2024 review of Ministry spending found there was a general trend of “no growth” in the number of clients served in supportive living since 2017-2018, and that this had contributed to the growing waitlist. The Financial Accountability Office reported that the number of people waiting for supportive living increased 49% between 2017-2018 and 2022-2023.[17]

88 Because of limited vacancies, DSO uses an algorithm to prioritize individuals for service, based on the associated level of risk to health or safety. A person’s risk level depends on their current living situation and their behavioural, personal, and medical support needs, as well as their caregiver’s circumstances. When a vacancy arises within MCCSS-funded supportive housing, DSO will first consider those with the highest priority scores for the vacancy.

89 A Matching and Linking Coordinator reviews the prioritized profiles to assess the best “match,” considering such factors as personal preferences, compatibility with any other residents in the home, and whether there are sufficient staffing levels to meet the person’s needs. However, DSO told us those with more complex needs often cannot be matched to existing funded vacancies. As one official in developmental services observed, Luc is “a perfect example of someone that cannot be matched within our group homes because he requires too much support.”

90 Some MOH-funded supportive housing, which is intended for individuals with serious mental illness or addictions, can also serve individuals with a dual diagnosis in certain circumstances. Demand for this housing also exceeds supply, although there is no standardized information about wait times. In 2016, Ontario’s Auditor General recommended that the Ministry regularly collect waitlist and wait time information by region.[18] Despite this recommendation, at the time of writing this report, the MOH still did not track wait times for supportive housing.

91 In the absence of provincially consolidated information about wait times, evidence suggests that individuals can face lengthy waits. A February 2024 report by the non-profit agency Addictions and Mental Health Ontario described multi-year waitlists for MOH supportive housing. That report notes that those with serious mental illness and complex needs who require 24-hour high support housing in Toronto, for example, may have to wait up to five years.[19] A March 2025 follow-up report by the same organization said waitlists were “at crisis levels.” They estimated that the average wait time for mental health supportive housing in Ontario was nearly four years, while in Toronto the average wait exceeded eight years.[20] The report also documents a growing need for high-support housing units, with a Toronto housing coordination agency reporting that 40% of applicants who were declined had needs that exceeded available service. It states that many of those waiting may be in shelters, hospitalized, or in housing that does not meet their needs.

Turned down and passed over

92 When DSO is unable to match people in urgent need to available MCCSS-funded vacancies, it refers them to a community planning table, and sometimes community tables in other jurisdictions, where ministry-funded service agencies in the area try to find or develop a solution. One senior official at an agency that helps connect families to available services said this referral was typically a “formality” rather than a solution for individuals like Luc or Noah, because agencies that are willing or able to support individuals with extensive complex needs are so scarce. A hospital’s Dual Diagnosis Coordinator in another region said that they have never had a long-stay patient with a developmental disability go into an existing funded supportive housing arrangement.

93 Individuals with the highest needs may instead have to rely on private agencies for supportive housing options. However, private agencies also struggle to provide the required capacity and resources. In Luc’s case, one private agency considered supporting him, but did not have sufficient staffing resources. Another did not have bilingual staff to provide the French service he requires.

94 Even if a private service agency offers to step in with a supportive housing space, the option may fall through because of lack of funding. In Anne’s case, when the hospital found a private agency willing and able to meet her needs, MCCSS funding was not available and she remained in hospital. Ministry staff in that region told us they would only fund private agencies as a last resort because they would rather build capacity within the funded system. However, by the time planning for Anne’s housing with a private agency collapsed, her case had already been presented to various planning tables throughout the region multiple times – and she’d been rejected for at least seven vacancies. Similarly, Jack’s profile was circulated to community planning tables for years, with no success.

95 These are not isolated cases. Hospital staff we interviewed and Ministry documents we reviewed[21] confirmed that individuals with developmental disabilities have been stuck in hospitals for periods of 10 years or more because no service agencies could be found to support them in the community.

Institutionalized in hospital

96 The longer someone with developmental disabilities remains in hospital, the more challenging it can be for them to transition to the community. Hospital staff told us the longer the hospital stay, the more reliant the person may become on higher staffing ratios and staff doing daily tasks for them. Over time, they acclimatize to hospital routines, and it becomes harder to establish or adapt to new ones. As one MCCSS official put it: “Experience has shown that the environment in which an individual is supported will condition their ability to adapt to living in the community.”

97 One hospital told us about a man in his 30s with an intellectual disability and significant mental health disability who had spent almost 14 years in hospital. They said the hospital determined that the man did not require hospital-level care shortly after he was admitted in 2009. Community planning tables considered his profile monthly for nearly eight years before an agency finally agreed to support his transition to the community. Unfortunately, he returned to hospital soon after, because the agency could not manage his behaviours. Hospital staff told us they believe the man had become “institutionalized” and came to think of the hospital as his home.

98 The loss of independence and life skills can increase the resources needed to support a person who has become institutionalized, making it more challenging for service agencies to plan for and support them in the community. A behavioural consultant who has worked in the sector for more than 20 years told us the people who get stuck in hospital have a “documented profile that can appear quite… difficult to support,” causing agencies to be hesitant to offer services. For example, unlike hospitals, developmental service agencies do not generally have the infrastructure or specialized staff necessary to respond when someone becomes extremely aggressive.

99 One MCCSS official explained that service agencies often “skip over” those with very complex needs – a vicious cycle that makes it more difficult for them to leave hospital as their stay continues.

100 Many of the cases highlighted in this report demonstrate the significant detrimental impact that a lengthy hospitalization can have. After years in hospital, Jack lost independence and increasingly required assistance with simple daily tasks. Noah lost his basic toileting skills and had been restrained in a hospital bed for so long, no one could predict how he would react outside of hospital. A service coordinator commented that “very, very few agencies would ever take somebody coming out of hospital in four-point restraints.” Even when an agency, moved by Noah’s compelling circumstances, finally offered him a home, his transition to the community was only possible with additional funding for renovations and added access to psychiatric and behavioural staff – and it took a further 15 months before everything was in place to allow him to move.

101 Ultimately, service agencies have discretion to determine whether they have capacity to support someone. MCCSS staff acknowledged that some service agencies do not want to assume the risk of someone with high behavioural needs harming staff, and said if a person transitions to a service agency that does not have the capacity to support them, there is a risk of doing more harm. We saw this in Anne’s case when she ended up in a hotel room unable to care for herself after moving into a ministry-funded home that did not meet her level of need. However, Ministry staff also said it is part of their oversight role to make sure agencies are considering more than their liability, as providing services to “vulnerable citizens” is “the bottom line of what [they] do.”

A “maxed out” system

102 Even when a service agency is willing to support someone with very complex needs, there is often just no appropriate space ready for them to move to or that could be converted to meet their needs. One MCCSS official told us that when institutions in the developmental services sector were closing between 1977 and 2009, steps were taken to create capacity to support people with high needs. The sector also created “unfunded capacity,” including an inventory of spare rooms, bedrooms, and other living units that could be used for future expansion. Unfortunately, this practice did not continue – and today, space in the sector is “maxed out.” Homes in the community are either fully occupied or the space is no longer suitable for new individuals to occupy because of changes in requirements like regulations, municipal by-laws, and fire safety codes. One Ministry official expressed concern that developmental services housing is at a “critical point,” as service agencies say there are no more spaces to convert.

103 The decreasing housing supply in the developmental services sector was predicted in an October 2018 Ministry Program Note.[22] It stated that service agencies had been asked to use available housing resources when undertaking multi-year planning to support the highest-priority individuals, “but system capacity will be reduced without additional investment to address rising costs and service demand.”

104 One Ministry official told us that now, “basically somebody has to pass away in order to create a vacancy.” The parents and service providers we spoke with made similar observations. Both Jordan and Jack were only able to leave hospital once a resident in a Ministry-funded home died. One MCCSS statistic from 2019 showed that each year, 1,500 new people request funded supportive accommodation, while only approximately 450 leave these spaces.[23]

105 The MOH does not track demand for its supportive housing programs, some of which we were told could support those with a dual diagnosis. However, a February 2024 report on mental health and addiction supportive housing stated that supportive housing providers were not confident that the system had capacity to support an increasing volume of people with complex mental health needs.[24]

A troubling trend

106 While the lack of appropriate housing is a long-standing issue in the developmental services sector, there are indications that the situation is getting worse. An April 2023 MCCSS Minister’s Briefing reported an 8% increase in the number of individuals with high support and complex support needs over the previous year.[25] It noted that the number of individuals with autism receiving funding through the Ontario Disability Support Program had increased by 5% between 2017 and 2022, with 20% of 18- to 24-year-olds with autism having “exceptional” behavioural needs. Another internal Ministry document from September 2021, related to the Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project, estimated that 20% of patients with dual diagnosis at Ontario’s psychiatric hospitals were designated as alternate level of care – and nearly half were waiting for community-based housing with a high level of support.[26]

107 One Ministry official candidly told us that, given the level of complexity and concurrent disorders, “the solutions we’ve been using are no longer meeting the needs of the people coming into the system now.”

108 Parents caring for their adult children with developmental disabilities at home are also aging. The April 2023 MCCSS Minister’s Briefing stated that 11,200 people with developmental disabilities live with a caregiver aged 60 or older, and this was expected to increase to approximately 17,400 over the next five years.[27]

109 It is troubling that the rise in the complexity of care needs and the aging population of caregivers come at a time when there are so few community resources available for those considered hardest to serve. The higher someone’s needs, the fewer resources there are. If these trends persist, inevitably, acutely vulnerable individuals with developmental disabilities will continue to languish in hospitals and other inappropriate settings. As we saw with the people featured in this report, many of those left in hospital will deteriorate mentally and physically and lose valuable life skills, making it harder and often more costly for them to transition to living in the community. At the same time, they will continue to occupy a bed that might be needed by someone in need of acute medical care. Families, hospital staff, and developmental services professionals will keep struggling to find solutions that do not exist, leaving the public to pay the price for a system that delivers the wrong care, in the wrong place.

Still Nowhere to Turn: Systemic Gaps

110 Nine years ago, in my 2016 report, Nowhere to Turn, I addressed the extremely troubling lack of suitable housing options for people with developmental disabilities who demonstrate aggressive or violent behaviours.[28] I also encouraged the Ministry to engage in research and consultation across the developmental services and health sectors. The aim of this was to develop supportive living resources that meet these individuals’ exceptional needs. I recommended that the Ministry create an inventory of suitable housing options, as the system was leaving many improperly housed in hospitals, shelters, long-term care homes, and even in jails.[29] The Ministry did conduct research on supportive living arrangements for individuals with exceptional medical and/or behavioural needs, but an inventory of housing to meet these needs remains lacking.

111 Since 2016, lack of supportive living spaces in the developmental services sector has continued to be a key barrier for those inappropriately housed in hospitals. As the Financial Accountability Office reported in 2024, there has been a trend of “no growth” in the number of people served within developmental services supportive living since 2017-2018.[30] The system remains reactive and fragmented.

Research on repeat

112 The lack of suitable housing options for those with developmental disabilities with complex or co-occurring needs is not a new issue. For more than a decade, researchers have warned about the problem, suggested solutions and called for action.

113 In 2009, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health published From Hospital to Home: The Transitioning of Alternate Level of Care and Long-stay Mental Health Clients.[31] The report, commissioned by the then-Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, found that a shortage of high-support housing, combined with “coordination challenges” between the health and developmental services systems, contributed to the hospitalization of people with dual diagnosis as alternate level of care patients. The Centre recommended that the ministries responsible for health and developmental services work together with those responsible for regional administration of public health care services to develop appropriate supportive housing options for people with dual diagnosis. It also encouraged greater communication and collaboration between the community and hospitals before these individuals are discharged, to ensure appropriate supports are in place.

114 In 2012, KPMG issued a report[32] commissioned by six Ontario psychiatric hospitals that assessed the hospital dual diagnosis programs and system gaps for those with dual diagnosis. It found that, amongst the six hospitals, this population accounted for 37% of alternate level of care patients. Participants in the review included physicians from hospital dual diagnosis programs and representatives from the Community Networks of Specialized Care. All identified limited access to supportive housing with adequate staffing levels and skills as a contributing factor to the high number of alternate level of care patients with dual diagnosis in hospitals. The report found there was a need for a broader range of housing, “especially for individuals with higher support requirements for their complex needs.”[33]

115 In 2014, the MCCSS created a Developmental Services Housing Task Force to research innovative solutions to the “severe housing shortage” in the developmental services sector. In 2018, the Task Force made recommendations to the Ministry about researching issues and inter-ministerial solutions to address situations faced by people with developmental disabilities, including those who have multiple needs or who are in complex or precarious housing situations, noting that the current approach was leaving thousands without the housing supports they need.

116 In February 2019, the Health Care Access Research and Developmental Disabilities program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, and the University of Ontario Institute of Technology released a report entitled Addressing Gaps in the Health Care Services Used by Adults with Developmental Disabilities.[34] They observed that patients with developmental disabilities are 6.5 times more likely to be classified as alternate level of care than others, and that this indicated problems with the availability or accessibility of appropriate community-based supports. The report also found that for those with both a developmental disability and mental health diagnosis, the likelihood and frequency of emergency department visits and hospitalizations increased.

117 In 2022, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health produced a Housing and Mental Health Policy Framework[35], which noted the particular challenges that alternate level of care patients with serious mental illness and complex needs have to access housing. The Framework includes a recommendation for MCCSS and MOH to work collaboratively to create targeted housing initiatives for individuals with dual diagnosis.

118 In 2023, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health published a report commissioned by the MOH through the Dual Diagnosis Alternate Level of Care Project, called Supporting Alternate Level of Care Patients with a Dual Diagnosis to Transition from Hospital to Home: Practice Guidance.[36] It echoed previous findings and recommendations, encouraging the health and developmental services sectors (including the two ministries and Ontario Health) to work together to establish and adequately resource a minimum set of core services for individuals with dual diagnosis. It suggested that these standard services should be available and accessible across the province and that there should be a range of housing and community support options with appropriately trained staff. The report also noted that data on population needs should inform decisions about housing models.

Progress hindered

119 Despite these repeated well-founded calls for action and recommendations for reform, negligible progress has been made to increase the availability of adequate supportive living accommodations in the community for people like Jordan, Sean, Jack, Luc, Noah, Anne, and Kevin.

120 In all the cases highlighted in this report, finding an appropriate Ministry-funded service agency or a private agency capable of providing support in the community for individuals with multiple or complex needs was a difficult and often years-long process. This was true even when individuals were identified as a high priority for receiving services in their communities.

121 Numerous officials across the health and developmental services sectors told us they were frustrated about the lack of suitable housing resources for these individuals. Some described the absence of suitable housing as the biggest barrier for those seeking to leave hospital. One hospital employee commented that trying to find a suitable home in the community for someone with a developmental disability, particularly someone with a dual diagnosis, was “virtually impossible.”

122 In Nowhere to Turn, I described hospitals as a Band-Aid solution to the problem of limited housing in the developmental services sector. I observed: “Today’s developmental services system does not reflect long-range strategic planning on the part of the Ministry, but rather a matrix of diverse and individualized visions of hundreds of non-governmental agencies involved in this sector.”[37]

123 After the release of that report, I saw some progress towards system planning to develop both developmental services housing and supportive housing generally. In 2017, the then-Ministry of Community and Social Services and the Ministry of Health collaborated with other ministries to create a cross-sector Ontario Supportive Housing Policy Framework.[38] The framework stated that supportive housing was key to enabling individuals with complex needs “to find stable housing, lead fulfilling lives, and live as independently as possible in their community.” Its stated goals included developing a more coordinated system where ministries, local entities like service managers, Local Health Integration Networks (now part of Ontario Health), housing providers and others worked together toward a more person-driven approach to meeting housing needs.

124 The MCCSS took some steps to address recommendations from Nowhere to Turn, including seeking ways to prioritize those with complex needs and investing in capacity building within the developmental services sector. By April 2018, it had developed a Developmental Services Housing Strategy[39] directed at increasing access to a range of person-centered, affordable housing and support arrangements to meet individuals’ unique needs.

125 That same year, the Ministry had also proposed an initiative intended to expand supportive living options specifically for prioritized individuals inappropriately housed in settings like hospitals, long-term care homes, and correctional facilities. The projected budget was $31 million. Under the initiative, there would have been dedicated resources for inappropriately housed individuals through the Multi-Year Supportive Living Program.

126 However, after a change in government and a government-wide cost-saving directive, the Ministry’s Assistant Deputy Minister of Business Planning and Corporate Services issued a memo to the MCCSS Management Committee asking all program areas to revisit their budget forecasts. Among other things, they were asked to slow down and scale back any spending, and revise program strategies to achieve savings, including by delaying implementation.[40]

127 In response, MCCSS staff prepared an Information Note for the Minister, setting out their expenditure management strategy for approval.[41] The items for which the Ministry would no longer seek funding included $25 million allocated for housing supports and $6 million in capital for inappropriately housed individuals. Other proposed initiatives – such as innovative housing, “living at home longer,” and new supportive living and respite spaces – were also removed from funding consideration.

128 At the same time in 2018, as the Ministry’s plans to seek funding for increased housing resources in the developmental services sector were abandoned, the Developmental Services Housing Task Force that the Ministry had created in 2014 was calling for a solution to the “crisis-driven approach to housing needs” in the sector. In its report, “Generating Ideas and Enabling Action: Addressing the Housing Crisis Confronting Ontario Adults with Developmental Disabilities,”[42] the Task Force emphasized that as housing waiting lists continue to grow, system planning must shift into “prevention” mode. The report assessed and analyzed 18 collaborative and innovative housing projects, some of which supported individuals with complex needs.

129 According to Ministry documents, MCCSS intended to evaluate those models to identify best practices that could be replicated with new investment in innovative housing and to fully leverage other community partnerships to increase the range of available housing. However, by July 2019, an internal Ministry Developmental Services Reform Foundation paper noted that MCCSS still did not have a broad strategy to “effectively and efficiently” reform supportive living services, which it said should include an official developmental services housing vision supported by stakeholders.[43]

Back on the back burner

130 The momentum that followed the release of my Nowhere to Turn report faltered and stalled. Efforts to address the problem continued, but progress has been slow and limited.

131 In 2020, a KPMG review of developmental services submitted to the MCCSS observed that Ontario was underperforming in “marketplace reform.” While the report said high-performing agencies were undertaking innovative initiatives, there was no mechanism to scale those initiatives across the province.[44]

132 That same year, the Central East Local Health Integration Network created a working group to seek more proactive solutions for people with a dual diagnosis who found themselves stuck in hospital. The working group, which included representation from MCCSS, reviewed the profiles of those who remained in hospital because they could not be served within the existing developmental service system. The working group was asked to find solutions that would ensure that individuals with dual diagnosis and high needs were served appropriately.

133 The working group reviewed data and patient profiles over several years. In 2021, they reported that patients in hospital with unmet housing needs often:

- Had developmental delay and multiple, separate mental health diagnoses;

- Were diagnosed on the lowest end of the autism spectrum (typically, non-verbal, or with very limited abilities);

- Required assistance with most aspects of daily living;

- Had elevated behavioural scores; and

- Had a history of aggression and/or criminal justice involvement.

134 The authors noted that the number of individuals within this profile was “relatively small.” The review also noted that the longer the hospital stay, the harder it was to find housing. Its list of key supports needed in the community for long-stay patients with complex needs include multi-organizational specialized clinical support teams, increased specialized housing, dedicated funding for housing renovations, cross-sectoral partnerships between disability and mental health supportive housing providers to ensure integrated supports and services, and a systems planner for housing.

135 Ontario Health officials familiar with the project told us the work done was “fantastic,” but progress stalled because of insufficient resources, staffing challenges, and shifting priorities.

136 In an internal document from 2022[45], MCCSS officials observed that supportive housing could reduce reliance on higher-cost government-funded services, “such as emergency room visits, hospital stays, police interactions, justice system involvement (including jail) and long-term care.” Another internal document from this period acknowledged that current housing capacity was insufficient and made several suggestions for reform. One was to leverage partnerships to increase affordable supportive housing with the proviso: “We can’t do it in silos.”[46]

137 Despite these multiple and extensive studies, there is still no detailed plan aimed at supporting those with developmental disabilities and other complex needs who cannot find suitable housing options. Many of the senior MCCSS staff we interviewed said they were unaware of any existing developmental services supportive living strategy.

138 There have been some efforts to develop a collaborative “Multi-Ministry Supportive Housing Initiative” for supportive housing, led by the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. But both the MCCSS and MOH described this as being in its “early stages.” The initiative is focused on supportive housing for “vulnerable populations” generally, and it is still unclear whether or how it will help to address the housing gaps for those with the most complex needs.

139 The MOH is also leading policy development for a Local Integrated Supportive Housing requirement under the Multi-Ministry Supportive Housing Initiative. Staff told us a draft policy is being developed and is intended to require health sector partners to work with municipal service managers and developmental services to plan supportive housing, rather than working in silos. This is similar to the multi-sector collaboration requirements in the 2017 Supportive Housing Framework. However, as of early 2025, Ministry of Health officials told us this work was on the “back burner,” as focus had shifted to rolling out Homelessness and Addiction Treatment Recovery Hubs to replace safe drug consumption sites. They said that supportive housing will be part of the hubs and some of that housing may support individuals with a dual diagnosis. However, they observed that it was unlikely to be of assistance for alternate level of care patients with developmental disabilities and complex needs, similar to those described in this report. It is also unlikely to assist those with developmental disabilities who do not have a mental health diagnosis or addiction.