Investigation into how the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services tracks the admission and placement of segregated inmates, and the adequacy and effectiveness of the review process for such placements

"Out of Oversight, Out of Mind"

Paul Dubé

Ombudsman of Ontario

April 2017

Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario

We are

An independent offce of the Legislature that resolves and investigates public complaints about Ontario public sector bodies. These include provincial government ministries, agencies, boards, commissions, corporations and tribunals, as well as municipalities, universities, school boards, child protection services and French language services.

Our Values

Fair treatment

Accountable administration

Independence, impartiality

Results: Achieving real change

Our Mission

We strive to be an agent of positive change by promoting fairness, accountability and transparency in the public sector and promoting respect for French language service rights as well as the rights of children and youth.

Our Vision

A public sector that serves citizens in a way that is fair, accountable, transparent and respectful of their rights.

Contributors

Director, Special Ombudsman Response Team

Director, Investigations

Lead Investigator

Investigators

- Chris McCague

- Grace Chau

- Rosie Dear

- Elizabeth Weston

- William Cutbush

Early Resolution Officer

Counsel

Press Conference:

Minister accepts all 32 recommendations:

Table of Contents

1 Twenty-four-year-old Adam Capay of Lac Seul First Nation suffered the intense isolation of segregation in Ontario’s correctional system for more than four years. If not for a fortuitous visit from the Chief Commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission to the Thunder Bay Jail in October 2016, he would likely still be confined alone in a Plexiglas-fronted cell where incessant bright lights blurred the line between night and day.

2 Adam Capay’s case reflects the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services’ inadequate tracking and review of segregation placements. When the Chief Commissioner asked for information about the duration of segregation placements, Adam’s – more than 1,500 days and now the longest known placement – wasn’t provided because the Ministry didn’t know about it. After his story emerged, without a reliable system for tracking segregation placements, the Ministry resorted to sending staff into the field to gather information about other prolonged segregation placements.

3 On any given day, about 560 of some 8,000 inmates in Ontario’s correctional facilities are segregated for 22 hours per day or more. Many are on “remand,” meaning they are facing criminal charges but have not been convicted.

4 Confining inmates in this manner is known by different names in different places: Segregation, solitary confinement, isolation, or separation. In Ontario, it is called segregation and is one of the most restrictive methods of imprisonment the government can impose. Some consider it torture, and the United Nations has said that placing inmates in solitary confinement for longer than 15 days is a form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment[1]. Clinical studies have recognized the health and suicide risks posed by extended segregation for all inmates, but especially those with mental health issues and developmental disabilities[2]. It is an unfortunate reality of today’s society that many of these individuals find themselves in the correctional system. Despite being particularly vulnerable to harm through segregation, they are routinely housed in isolated cells for safety and security reasons or because corrections officials don’t have more appropriate options for housing them.

5 The Ministry’s policy – which governs all “special management” inmates, not just those in segregation – provides segregated inmates with legal safeguards to ensure their situations are regularly reviewed and, on paper, requires that senior officials approve all lengthy segregation placements. Theoretically, an inmate should only be placed in segregation as a last resort after every other option has been exhausted. In practice, the policy requirements are often ignored.

6 My investigation found numerous examples where correctional facilities failed to accurately track how long inmates had been kept in segregation. For instance, the Ministry identified five different segregation start dates for Keith,[3] who was segregated in dozens of different locations for more than a year, until he was moved from a dark, dirty cell into a newly created unit where he was afforded greater privileges in exchange for his good behaviour. The Ministry’s struggles to accurately track segregation placements are compounded by the confusion and disagreement around what segregation actually means. In dozens of interviews, correctional staff and Ministry officials expressed conflicting understandings of what conditions of confinement and placements amounted to segregation. Human error and insufficient procedures also account for incomplete and inconsistent records. As one Ministry official put it to us: “We probably tracked livestock better than we do human beings.”

7 The Ministry’s review of segregation placements to ensure compliance with regulation and policy is also patently deficient. We discovered numerous instances in which inaccurate and inconsistent information was used to justify and explain the lengthy segregation of vulnerable inmates. We found that too often superficial review exercises precluded any meaningful evaluation of individual inmate circumstances; in some cases, reviews of ongoing segregation placements were wholly inadequate. For instance, we found one inmate, Harry, naked and in a dishevelled state in a dirty cell. He had been in segregation for more than 30 days. However, when we reviewed the relevant documentation, we found that successive segregation review forms referenced incorrect information, were virtually carbon copies of each other, failed to record his severe mental illness, and suggested that no actual review or update of his initial assessment had ever taken place. Similarly, the lawyer of a first-time inmate, Linda, alerted us to her deteriorating state in segregation. Linda is over 65 years of age and lives with a physical disability as well as significant mental health issues that require careful monitoring in segregation. Yet her segregation records revealed numerous significant deficiencies, including inconsistent and inaccurate references about whether she even had any disabilities.

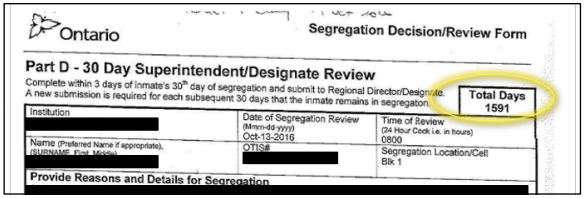

8 The flawed state of the Ministry’s practices and policies regarding segregation of inmates has not gone unnoticed or unremarked. In 2013, the Ministry settled a human rights complaint and committed to a comprehensive review of its use of segregation[4]. In 2015, it began a review and consultations on this subject. In the wake of public disclosure of Adam Capay’s circumstances in October 2016, it announced an overhaul of the use of segregation, and appointed an independent reviewer to examine comprehensive reforms to the correctional system.

9 As Ombudsman, I have the authority to investigate the Ministry’s 26 correctional facilities. My Office receives thousands of complaints about them every year, including hundreds about segregation. Given our practical experience in this area, I shared our insights by publishing a submission in May 2016 entitled Segregation: Not an Isolated Problem, which made 28 recommendations for reform. Since then, we have continued to track segregation-related complaints. After witnessing an alarming increase in the number of these complaints and examining Adam Capay’s situation, it was clear to me that serious systemic concerns persisted. Accordingly, on December 1, 2016, I notified the Ministry that I would be investigating how it tracks segregated inmates, and the adequacy and effectiveness of its review process. I have concluded based on the results of my investigation that the Ministry’s tracking and review of segregation placements is unreasonable, wrong, oppressive, and contrary to law under the Ombudsman Act. This report makes 32 recommendations for reform, including that the Ministry appoint an independent panel to review all segregation placements.

10 My findings will not be news to the Ministry. Officials we interviewed candidly admitted that they could not trust the inconsistent and contradictory segregation data generated by correctional facilities. They also recognized that segregation reviews conducted by frontline officers and regional Ministry staff were typically pro-forma exercises. What this investigation has made abundantly clear is that vigorous and credible oversight mechanisms need to be put in place to enforce the regulation and policy, as well as to ensure respect for inmates’ human rights.

11 While the Ministry is now taking steps to improve its segregation practices, considerably more is required, and on an expedited basis. It has a responsibility to ensure the health and welfare of those incarcerated in its correctional facilities. Improving the tracking and review of segregation is a fundamental and foundational step towards better accountability, fairness and integrity in Ontario’s correctional system.

12 My Office has closely monitored the issue of segregation since early 2013, when we were contacted by an inmate at Central East Correctional Centre who complained he had been held in segregation for almost three months without a valid reason. When we asked for information to understand why the inmate remained in segregation, neither the facility nor the regional Ministry office could provide any documentation to show that the required reviews had been carried out. This was deeply troubling because the regulation under the Ministry of Correctional Services Act and Ministry policy require correctional facilities to complete segregation reviews every five days, with additional review by the regional office every 30 days.

13 Since this complaint, my Office has been concerned about the adequacy and effectiveness of segregation tracking and reviews. We closely monitored and resolved individual complaints from segregated inmates – more than 550 over a three-year period. Some of the stories we heard from these inmates were harrowing. An inmate who spent more than three years in segregation at various facilities complained to us that he was depressed and “sick of life.” In another case, when we tried to follow up with an inmate who had complained that he was “distressed” at being told he would serve his entire sentence in segregation, we learned he had taken his own life. Another who had been in segregation for three consecutive months and a cumulative total of nine, complained that he could not eat or sleep and feared he was losing his mind. When we made inquiries about these concerns, we found some senior staff were not even aware of the segregation review and reporting requirements. In one instance, we discovered a manager had even attempted to replicate missing reports.

14 These concerns were made public in my Office’s annual reports in 2014 and 2015. My staff also met with senior Ministry officials and highlighted 15 egregious cases, focusing on the lack of required reviews and reliable data, as well as the impact of prolonged segregation on vulnerable inmates. Although the Ministry worked to resolve individual cases and committed to improve, progress was slow and incomplete and we continued to see many instances where the reporting requirements had either not been met or were not documented properly.

15 In March 2015, then-Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services Yasir Naqvi announced “a comprehensive review of the segregation policy and its use in correctional facilities, including how it interacts with our other mental health policies”[5]. Having received hundreds of complaints from segregated inmates, we had seen the impact and effects of segregation, and were uniquely positioned to provide valuable input.

16 Based on this experience, we prepared a written submission for the Ministry – Segregation: Not an Isolated Problem, published in May 2016 – containing 28 recommendations[6]. I personally met with senior Ministry officials to present my recommendations and discuss the use of segregation in the province. The key recommendations in our submission were to abolish indefinite segregation, establish independent review and oversight, and develop alternative housing and programming to meet the needs of vulnerable inmates.

17 I urged the Ministry to take a broad, transformative approach to the use of segregation in the province, suggesting that mental health assessments, as well as treatment and reintegration plans, be mandatory for all segregated inmates. I noted the importance of clearly defining segregation and focusing on the conditions of an inmate’s confinement. I also called on the province to provide independent and impartial reviews of all segregation placements. I recommended that an independent panel hold hearings within the first five days of each placement to ensure that it is justified and used only as a last resort. The panel would be required to take the inmate’s well-being into account, and inmates would be provided access to counsel and a rights advisor.

18 I further urged the Ministry to train staff on inmates’ rights and the harmful effects of segregation, and to collect, analyze and report annually on statistics about the use of segregation across the province. In addition to the independent adjudication process, I recommended the Ministry regularly review segregation placements to ensure they are in accordance with regulation and policy. I also recommended that all procedural protections for segregated inmates be incorporated into legislation, rather than policy or Ministry directive.

19 This submission received considerable media coverage, and other expert stakeholders – including the Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada (which oversees the federal prison system) and the Ontario Human Rights Commission – agreed that placing inmates in segregation for long periods of time is cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment. Our recommendations reflect the minimum standards set out by the United Nations in its Nelson Mandela Rules, which prohibit indefinite (15+ days) placements in solitary confinement.

20 Segregation-related complaints to our Office increased from April 1 to December 1, 2016: We received 183 complaints in this period – nearly as many as we had received in the previous 12 months.

21 In October 2016, the Chief Commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission was visiting the Thunder Bay Jail when she discovered Adam Capay, 24, who was awaiting trial on a murder charge. He had been in segregation for more than 1,500 days – four years and counting – yet the Ministry had neglected to include his placement in the statistics it had provided to the Commission regarding segregation placement durations. He was living in a Plexiglas-fronted cell under bright lights, which never dimmed. Shortly after hearing about this case, I sent investigators to Thunder Bay to look into his circumstances. What they found was greatly concerning, and together with the high volume of complaints we had received, confirmed that the use of segregation remained a serious systemic issue. Accordingly, I asked our Special Ombudsman Response Team to begin identifying the issues and drafting an investigation plan.

22 While this planning process was ongoing, the government announced it would “begin an overhaul” of the use of segregation[7]. The Ministry appointed Howard Sapers, the former Correctional Investigator of Canada, to examine the use of segregation and recommend comprehensive reforms to the broader correctional system. The stated targets of the review included reducing the number of people in segregation and the length of those placements, improving the conditions of confinement for segregated inmates, developing appropriate alternative placements for vulnerable inmates, and improving oversight of inmates and correctional institutions[8].

23 As part of the overhaul, the Ministry also implemented several immediate changes, including:

-

Limiting “disciplinary” segregation of inmates to 15 consecutive days, reduced from the previous maximum of 30 (there was still no limit on segregation for non-disciplinary reasons);

-

Establishing weekly meetings of a segregation review committee at each institution, to assist in arranging alternative housing placements and otherwise improving the conditions of confinement;

-

Reviewing data collection practices; and

-

Assessing existing capital infrastructure relating to segregation.

24 Although I was encouraged by the Ministry’s commitment to reform and applaud the appointment of Mr. Sapers as independent reviewer, I continued to believe the Ministry’s use of segregation was a serious, systemic problem that required further investigation. After years monitoring this issue and watching the Ministry initiate serial reviews, the time for incremental change and further study was over and my Office’s unique expertise to investigate and report on this issue was required.

25 On December 1, 2016, I notified the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services that I was launching an investigation into how the Ministry tracks the admission and continued placement of inmates in segregation in provincial correctional facilities, and the adequacy and effectiveness of the review process of such placements. The following day, I publicly announced the investigation. Between December 2, 2016 and March 31, 2017, we received another 87 complaints related to segregation.

26 I chose to focus my investigation on these specific issues for several reasons. Many complaints my Office received from segregated inmates demonstrated clear deficiencies in the tracking and review process for their placements. After repeatedly seeing the same errors, it appeared that the issue was clearly systemic. And unlike many of the other issues facing Ontario’s correctional facilities – aging infrastructure, staff shortages, increasing numbers of inmates with mental illness – I believed that enhancing segregation oversight by improving the tracking and review of placements would not require years of planning and major financial investment. I also knew that focusing on two distinct issues would allow my investigators to move quickly during the investigation and produce a thorough and timely report. Given the serious adverse effects segregation can have on individuals, time was of the essence.

27 Six investigators from our Special Ombudsman Response Team, assisted by members of our Legal team and one Early Resolution Officer, conducted 36 interviews with Ministry and correctional staff. Investigators visited four correctional facilities of varying age, type and size across the province: Central East Correctional Centre, Elgin-Middlesex Detention Centre, Thunder Bay Jail and Vanier Centre for Women.

28 Investigators also reviewed some 8,000 pages of printed documents and 2,000 electronic documents, including relevant policies, directives, statistics, training materials, internal communications and other information provided by the Ministry at my request. As well, we looked at how segregation placements are tracked and reviewed in other jurisdictions across Canada and in other countries.

29 Staff attended two briefing sessions by the Ministry about its ongoing segregation-related initiatives. These sessions provided information about a new tool intended to better track segregation placements, as well as the Ministry’s plan to increase staffing levels and invest additional resources in Ontario’s correctional system.

30 Throughout the investigation, I communicated with Mr. Sapers, the Ministry’s independent reviewer, regarding my ongoing observations and preliminary findings. I spoke with Mr. Sapers informally on several occasions, and on January 30, 2017, I gave a presentation to the Deputy Minister, senior Ministry staff, and Mr. Sapers regarding the issues identified during the first 60 days of my investigation. It is common to provide an update to a Ministry during the course of an investigation; in this case, I also wanted Mr. Sapers to have the benefit of the information we had gathered.

31 We received excellent co-operation from the Ministry and correctional staff during the course of the investigation.

32 The provincial Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services is responsible for 26 adult correctional facilities, which house:

(a) People who are waiting trial or sentencing, i.e., they are accused of criminal offences but have not been convicted or sentenced;

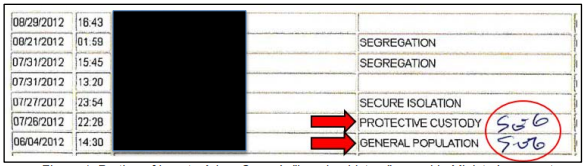

(b) People held for immigration hearings or deportation;

(c) People who have been convicted and sentenced to periods of incarceration ranging from a few days to a maximum of two years less a day (people sentenced to terms of two years or more are housed in prisons that are the responsibility of the federal government); and

(d) People awaiting transfer to federal institutions.

Regulation 778 under the Ministry of Correctional Services Act, the Ministry’s “Placement of Special Management Inmates” policy, and recent Ministry directives govern the use of segregation in Ontario[9].

33 The regulation, portions of which are included in this report at Appendix A, does not define “segregation.” Rather, a general policy governing all “special management” inmates sets out a meandering definition, which provides that segregation is:

"[A]n area (for administrative segregation or close confinement housing, inmates are confined to their cells, limited social interaction, supervised/restricted privileges and programs, etc.) designated for the placement of inmates who are to be housed separate from the general population (including protective custody, special needs unit(s), etc.)[10]."

34 Under section 34(1) of the regulation, an inmate may be placed in segregation if:

(a) in the opinion of the Superintendent, the inmate is in need of protection;

(b) in the opinion of the Superintendent, the inmate must be segregated to protect the security of the institution or the safety of other inmates;

(c) the inmate is alleged to have committed misconduct of a serious nature; or

(d) the inmate requests to be placed in segregation.

35 Placing an inmate in segregation for one of these reasons is referred to as “administrative segregation.” It is the most common form of segregation in the province and is potentially indefinite in duration. Ministry policy defines this form of segregation as:

"[T]he separation of an inmate (placement in segregation) from the general population (including protective custody, special needs unit(s), etc.) where the continued presence of the inmate in the general population would pose a threat to the health or safety of any person, to property, or to the security or orderly operation of the institution[11]."

36 The second form of segregation, “close confinement”, is used to discipline inmates for serious institutional misconduct[12]. The Ministry announced in October 2016 that placements in close confinement are now limited to 15 consecutive days, although the regulation has not been updated and reflects the previous maximum of 30 days[13]. Ministry policy defines this form of segregation as:

"[t]he separation of an inmate (placement in segregation) from the general population (including protective custody, special needs unit(s), etc.) where it has been determined as the result of a disciplinary proceeding that the inmate has committed a misconduct of a serious nature[14]."

Forms of segregation in Ontario correctional facilities

| Type |

Used When |

Time Limit |

Conditions |

|

Administrative Segregation (non-disciplinary)

|

-

Inmate needs protection

-

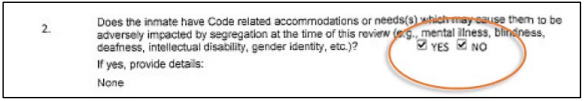

Inmate poses threat to health and safety of any person, property or security or orderly operation of institution

-

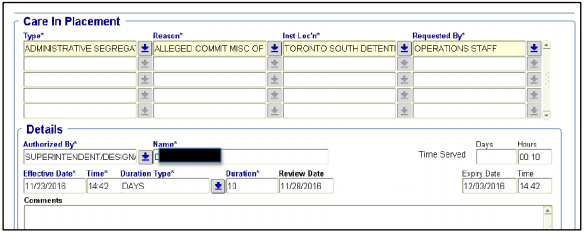

Inmate is alleged to have committed a misconduct of a serious nature[15]

-

Inmate requests to be placed in segregation

|

No limit

|

-

Same basic rights and privileges as other inmates

-

Conditions vary across institutions as determined by staffing, access to programs, availability of facilities

|

|

Close Confinement (disciplinary)

|

|

15 days

|

|

37 Most inmates in long-term administrative segregation have requested it, usually because they do not feel safe on a regular unit. According to an internal report produced by the Ministry for the 2015-2016 fiscal year, 52% of inmates who had been continuously segregated for 30 or more days requested the placement. Some 33% were segregated because the inmate required protection, 13% for security reasons, and 2% because they were accused of serious misconduct.

38 I recommended in my May submission that the Ministry address the underlying issues that result in inmates asking to be placed in segregation. It is our Office’s experience that many inmates request segregation because they fear for their safety. Regardless of the reason why an inmate is in segregation, it should always be considered a last resort. The Ministry is not relieved of its obligations to review segregation placements as required by regulation and Ministry policy simply because an inmate has requested the placement.

39 Once an inmate is placed in segregation, regulation and policy mandate that the correctional facility’s Superintendent or designate review the placement on a strict schedule. These reviews are primarily documented on a form called a “Segregation Decision/Review Form,” included as Appendix B. The schedule is as follows:

24-hour review:

Within 24 hours of an inmate being placed in segregation, the superintendent or designate must conduct a preliminary review of the placement. The inmate must be advised of the reasons and duration of the segregation, as well as the right to make submissions about the placement[16].

5-day review:

Every five days, the superintendent or designate must review the full circumstances of the inmate’s placement to determine whether the inmate’s continued segregation is required[17].

30-day review:

If an inmate is placed in segregation for a continuous period of thirty days, the superintendent or designate completes a further review of the inmate’s segregation. This review is submitted to the regional director or designate who also reviews the placement to determine whether continued segregation is supported. This review is documented on “Part E” of the Segregation Decision/Review Form and returned to the correctional facility. In addition, a regional 30-day segregation report must be forwarded to the Assistant Deputy Minister for Institutional Services (to be reported to the Deputy Minister)[18].

60-day review:

The superintendent or designate must track whether an inmate has been in segregation for 60 aggregate days in one year. When this threshold is met, the superintendent or designate must submit a report to the regional director or designate advising whether the inmate has a mental illness or other Human Rights Code-related needs that may cause them to be adversely impacted by a prolonged period of segregation (e.g., cognitive, emotional, social functioning and physical functioning). It must also detail the reasons for continued segregation, as well as any alternatives considered and attempted to integrate the inmate out of segregation. The regional director or designate must report these placements to the Assistant Deputy Minister for Institutional Services[19].

40 The regulation and policy provide that inmates placed in segregation for non-disciplinary purposes retain, “as far as practicable,” the same benefits and privileges as if they were not placed in segregation[20].

41 The policy also contains additional provisions intended to provide enhanced procedural protection for inmates placed in segregation. It emphasizes the Ministry’s duty to accommodate inmates under Ontario’s Human Rights Code, especially those with mental health concerns. These requirements were implemented as a result of the human rights settlement entered into with former inmate Christina Jahn[21].

42 The policy states that segregation cannot be used for inmates with mental illness and/or intellectual disability unless the facility can demonstrate and document that all other alternatives to segregation have been considered and rejected because they would cause an undue hardship[22]. If the threshold of “undue hardship” is met and an inmate with mental illness and/or intellectual disability is placed in segregation, additional protections apply. A physician must conduct a baseline assessment of the inmate when they are placed in segregation, and a mental health provider must assess the inmate at least once every 24 hours[23]. Prior to each 5-day review, a physician or psychiatrist must assess the inmate’s mental health[24].

43 The policy also provides for mental health screening on admission, the creation of inmate “treatment plans”[25] and/or “care plans”[26] in certain instances, and increased officer training. Senior administration is required to visit inmates in the segregation unit at least once in every three-day period[27].

44 The United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on Torture has clearly stated that lengthy segregation can amount to torture[28]. Based on this conclusion and input from others, in May 2015 the United Nations declared that placing inmates in segregation for longer than 15 days is a form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment[29]. The deleterious effects on inmates arising from prolonged isolation have also been documented in numerous clinical studies[30]. Recently, the College of Family Physicians of Canada called for a ban on solitary confinement in prisons, noting that its use can have a negative impact on a person’s health, can worsen pre-existing conditions, and can be especially detrimental for inmates who suffer from mental illness[31].

45 Policies and regulations are only effective if they are understood and followed. My investigation found that a fundamental pillar of Ontario’s approach to segregation – the definition of segregation – is confusing and provides insufficient guidance to frontline and senior Ministry staff. Since only “segregation” placements are subject to reporting and tracking requirements, it is important to have a clear definition of segregation that is applied consistently throughout the province.

46 The definition of segregation, which exists only in Ministry policy, primarily treats it as a physical place to confine inmates, rather than the conditions of confinement. This is troubling, since only inmates who are “segregated” qualify for the procedural protections guaranteed in regulation and policy, which represent an important check and balance against indiscriminate and arbitrary use of the authority to segregate inmates.

47 Our investigation found numerous instances where correctional and Ministry staff faced challenges in applying the existing definition of segregation to the situations they encountered on a daily basis. We discovered that the name of the unit in which an inmate is placed is significant. If the unit is not labelled as a segregation area, inmates may have no access to the required procedural protections.

48 For instance, in late 2016, we received complaints from three inmates at South West Detention Centre who said that they were only allowed out of their cells for two 40-minute periods each day. Even then, they were isolated from other inmates. Typically, inmates in general population are allowed out of their cells during the day except for meal times. Our Office spoke with the centre’s superintendent, who confirmed that inmates in the “Behavioral Management Unit” were only permitted to leave their cells during “rotational unlock,” one at a time, for short periods each day.

49 Although it was clear that these inmates were separated from the general population, confined to their cells for more than 22 hours a day, and had almost no social interaction, the centre did not consider them to be “segregated.” Officials there told us they arrived at this conclusion without consulting regional or senior Ministry staff. However, since the inmates were not considered segregated, they were not entitled to make submissions about their placements. No reviews were conducted by the centre or the Ministry to confirm whether the inmates’ continued placement in the unit was supported. After my Office’s involvement, the centre changed its practice and now requires that inmates receive at least three hours outside of their cells each day. According to an inmate who complained to us, inmates are out of their cells as a group for more than seven hours each day, effectively ending their segregation-like conditions.

50 Other correctional facilities have developed similar “non-segregation” units where inmates are removed from the general population and their social interaction limited. The Vanier Centre for Women has an “Intensive Management, Assessment and Treatment” unit where inmates spend varying amounts of time outside their cells based on their individual circumstances. While the purpose of this unit is to support inmates with complex behavioural and mental health needs, the result is that some inmates are kept in segregation-like conditions without any of the accompanying procedural protections.

51 Our investigation revealed units by several other names – special handling, special needs, mental health, “step-down” – where inmates may be subject to isolating conditions. In general, Ministry and correctional officials did not consider inmates in these units to be segregated, and they are thus not usually reported in segregation statistics or entitled to any review of the conditions of their confinement.

52 Given the ineffective and confusing definition of segregation, we learned that some Ministry and correctional staff are now relying on a “two-hour threshold” to determine whether an inmate is segregated. Under this approach, inmates who are allowed out of their cells for at least two hours a day are not considered segregated, regardless of where they are housed. This threshold reflects the United Nation’s definition of solitary confinement, which refers to confining inmates for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact[32]. However, there is no reference to a two-hour threshold anywhere in the regulation, Ministry policy or directives. In addition, it does not appear to take into account whether inmates are given the opportunity for meaningful human contact while out of their cells.

53 As well, it is not universally accepted or applied. For instance, staff at the Thunder Bay Jail told us that prior to October 2016, they considered their special handling unit to be a form of segregation, and they completed periodic segregation reviews for each inmate. However, in October 2016, a Deputy Regional Director told them this was not necessary, because inmates in this unit were allowed out of their cells daily for more than two hours – although they were removed from the general population. In response, the jail discontinued its segregation reviews for these inmates. However, on November 1, the regional office asked the jail to continue completing the reviews. Then, in January 2017, the Ministry’s corporate office reversed this position, telling the jail that placement in the special handling unit was not considered segregation, and the jail ceased conducting reviews. One more apparent reversal came when we spoke to the Associate Deputy Minister on January 31, 2017: She said this instruction was wrong and needed to be corrected.

54 There is also uncertainty about what amounts to a “continuous” segregation placement. Ministry policy requires that certain reports be completed after 24 hours, 5 days, and 30 days of continuous segregation. There is no clear explanation of what “continuous” segregation entails. For example, we found an internal Ministry email in which an employee asked if a one-hour break in segregation would reset the time for calculating continuous segregation. No definitive answer was offered.

55 In the absence of Ministry guidance, some staff told us they have developed an informal “24-hour rule,” whereby segregation is not continuous if there has been at least a 24-hour break in the placement. As with the “two-hour threshold,” this is not codified in Ministry policy or directive.

56 Many correctional and Ministry staff we interviewed called for greater clarity in defining segregation and continuous segregation. Most said they were familiar with the two-hour threshold and 24-hour rule, but were uncertain about where they originated and whether they should be followed. As one senior Ministry official put it: “There’s a huge confusion on [what is] segregation and what’s not.”

57 Much of the confusion about defining segregation in Ontario stems from the fact that Ministry policy conceives of segregation as a physical place. In contrast, the United Nations’ Standard Minimum Rules on the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules) refer to the conditions of confinement. They specify that solitary confinement (i.e., segregation) means “confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact”[33]. Our investigation looked at several jurisdictions that have taken a more practical approach to defining segregation.

58 In Scotland, “administrative segregation” occurs when an inmate is “removed from association” with other inmates[34]. Norway’s definition also focuses on whether an inmate is able to interact with other inmates; there, segregation is “exclusion from [the] company of other prisoners”[35]. In Manitoba, segregation is defined as “the confinement of one or more inmates…in a manner that prevents their physical contact with other inmates”[36]. (Lockdowns, which involve temporarily confining inmates to their sleeping areas and restricting entry to the facility for assorted safety and security reasons, are excluded[37]).

59 Although there is no universal definition of segregation, definitions that describe the conditions of confinement are preferable because they address underlying concerns related to the harm caused by isolation. The Ministry should adopt a new definition of segregation based exclusively on how, not where an inmate is confined or what the unit is called. The revised definition should be in accordance with international standards, which define segregation as the physical isolation of individuals to their cells for 22 or more hours a day. It should provide precise guidance to correctional staff about what does and does not qualify as segregation, so it can be consistently applied across the correctional system. The Ministry should also clarify whether temporary lockdown of a group of inmates comes within the definition, and whether this changes based on the length of the lockdown.

Recommendation 1

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should revise the definition of segregation to ensure that it encompasses all inmates who are held in segregation-like conditions. The revised definitions should be in accordance with international standards, which define segregation as the physical isolation of individuals to their cells for 22 to 24 hours a day.

Recommendation 2

The Ministry’s revised segregation definition should clearly indicate whether confining a group of inmates to their cells (e.g. lockdowns) comes within the definition.

60 The Ministry should also clearly set out what constitutes a “continuous” segregation placement. For example, in the federal prison system, the Correctional Service of Canada has developed detailed rules for determining whether a segregation placement is “continuous.” These rules are codified in a commissioner’s directive and provide that a segregation placement is considered “continuous” if an inmate is out of segregation for less than 24 hours, regardless of the reason why they are readmitted[38]. When an inmate is released from administrative segregation (as opposed to confinement for disciplinary reasons) for more than 24 hours, the placement is still considered continuous if the inmate does not successfully reintegrate into general population or if they are re-segregated for the same reason. The directive further clarifies whether specific situations – e.g. temporary absences for court appearances, facility transfers, hospital visits – are considered for the purpose of calculating “continuous” segregation placements.

61 Prior to adopting the revised definition, the Ministry should consult with frontline correctional staff to ensure the definition can be easily, accurately, and consistently applied at Ontario’s various correctional facilities. Consistency in applying the definition is key in ensuring fair access to procedural protections as well as the overall integrity of segregation-related statistics produced by the Ministry.

62 To ensure the definition is adequately understood and applied consistently, correctional officials from all organizational levels should receive training on the revised definition that includes examples of how it applies to different scenarios commonly occurring in facilities.

Recommendation 3

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should clearly define what constitutes a break from segregation for the purposes of determining whether a segregation placement is continuous.

Recommendation 4

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should consult with frontline correctional staff to ensure that any proposed definition can be easily, accurately, and consistently applied at Ontario’s various correctional facilities.

Recommendation 5

Correctional officials from all organizational levels should receive training regarding the revised definition for segregation. This training should include examples of how the definition applies to different factual scenarios that commonly occur in correctional facilities.

63 Given the importance of this definition and the potential adverse affects that segregation can have on inmates’ health and welfare, the revised definition should be codified in legislation, with additional guidance set out in a separate segregation policy. Currently, policies regarding segregation are set out in a general policy governing all “special management” inmates.

Recommendation 6

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should codify the revised segregation definition in the Ministry of Correctional Services Act or its regulation. Additional interpretative guidance regarding the application of the definition should be set out in a separate segregation policy.

64 The Ministry should implement the revised segregation definition as soon as possible, and no later than six months after receiving this report. The protection of inmates who are kept in isolating conditions should not depend on the name of the unit they are housed in. The accuracy and consistency of segregation statistics are also dependent on all Ministry and correctional staff having a clear, shared understanding of what qualifies as segregation.

Recommendation 7

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should implement a revised definition of segregation as soon as possible, and no later than six months after receiving this report.

65 As the case of Adam Capay demonstrates, the Ministry has not developed an effective system for tracking inmates in segregation. There are several factors contributing to this failure including the existence of multiple tracking methods, lack of communication between different correctional facilities, and limited reporting requirements. When the Ministry’s tracking fails, inmates can fall through the cracks and languish in segregation without the knowledge or oversight of senior Ministry officials.

66 Keith is an inmate at the Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre (OCDC) who was in segregation for more than a year. We discovered that the Ministry’s records contain at least five different start dates for his segregation placement – ranging from October 28, 2015 to June 23, 2016.

67 We confirmed that Keith was admitted to OCDC on October 28, 2015; at the time this report was written, he remained there. According to the Ministry, Keith initially requested to be placed in segregation because he had an injured shoulder and he feared for his life due to “gang affiliations.” He has no diagnosed mental illness, but correctional staff noted in his record that he had “apparent mental health issues” and “presented as having diminished cognitive ability and found it difficult to answer any questions or carry on a conversation.”

68 The Ministry’s own review found that Keith’s segregation cell (as of November 2016) was “extremely dirty and dark,” although this concern was subsequently addressed. It was not until January 9, 2017, that he was moved out of segregation to a newly created “step-down” unit. Step-down units do not have a set definition in Ministry policy, but are intended to house inmates who require higher levels of supervision and support than what is offered in the general population. The ultimate goal is for these inmates to “step down” and safely return to a regular living unit.

69 Inmate placements are documented in the “housing history” section of the Ministry’s Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS). Keith’s housing history documents a few dozen unit and cell changes during his time at OCDC. The stated reasons for these placements vary: Some are labelled “segregation,” others “protective custody,” one very short placement (lasting less than an hour) is called “general population,” and one eight-day placement is called “secure isolation.” Despite the varying terminology, most of these placements were clearly segregation.

70 As part of the Ministry’s review of all inmates segregated continuously for more than a year, its Program Effectiveness, Statistics and Applied Research (PESAR) unit prepared a spreadsheet containing the start dates of every lengthy segregation placement. That spreadsheet showed Keith’s segregation start date as November 1, 2015, which meant that he had spent 360 days in segregation at the time of the Ministry’s review. However, PESAR’s report also showed his “possible alternate” segregation start date was October 28, 2015.

71 Ministry staff went to OCDC in November 2016 to interview Keith, review his file, and complete an executive summary about his placement. But this review added to the confusion with a report including these contradictory statements:

-

“[Keith] has been in Segregation at OCDC since October 28, 2015.”

-

“Date admitted to Segregation: October 30, 2015.”

-

“November 1, 2015: date of inmate admission to Seg – Seg Decision Review form.”

-

“Institution seg file commences Feb 19, 2016 as there was an attempt to move [Keith] to a general living unit, however he only lasted hours.”

-

“Institution seg file commences Feb 19, 2016 as there was an attempt to move [Keith] to a general living unit, however he only lasted hours.”

-

“February 19, 2016: Segregation Decision Review form – initial placement completed.”

72 In response to our questions about this file, the Ministry confirmed that OCDC “started [Keith’s] segregation time over” on February 19, 2016, even though he was only out of segregation for a few hours. That was not the end of the confusion; our investigation found other instances where OCDC also recorded Keith’s segregation start date as June 23, 2016.

73 Our investigators also reviewed the housing history of Adam Capay, who was segregated for more than four years. Although he was in segregation continuously throughout that time, his housing history describes his placement not just as “segregation,” but also, at various times, as “protective custody,” “general population,” and “secure isolation.”

74 Each time an inmate is moved and the new placement is entered in the computer system, jail staff must select the type of housing from a drop-down menu. Evidently, the wrong option was selected in some of these instances. These errors were not discovered until our investigators spoke with a senior correctional staff member, who then added a handwritten note confirming that Adam’s last two entries should have reflected that he was in segregation.

Figure 1: Portion of inmate Adam Capay's "housing history" record in Ministry's computer system indicates different descriptions of his placement. An employee hand-corrected this after we pointed out the errors, adding the notation "SEG" for “segregation.”

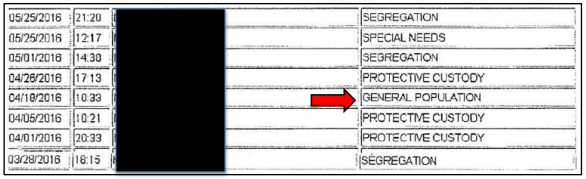

75 We discovered similar errors at a different facility in the housing history of Theresa, another inmate who spent an extended period in segregation. Her segregation placement was described at different times as “segregation,” the “special needs” unit, “protective custody,” and even “general population.” These inconsistencies were again attributed to human error in selecting the right location from a drop-down menu. Because facility staff did not correctly record Theresa’s placements, they were not initially able to calculate her time in segregation correctly.

Figure 2: Portion of inmate Theresa's housing history, showing different descriptions for her placement, including "general population."

76 One of the reasons the Ministry’s segregation tracking data is so unreliable is that it is documented in numerous ways at the facility and Ministry level. These include:

-

Log books updated manually by correctional staff;

-

30-day Segregation Decision/Review forms sent to regional Ministry officials;

-

Daily segregation counts submitted by each institution to the Ministry’s statistics unit (PESAR);

-

Data entered in multiple areas of the Ministry’s computer system (Offender Tracking Information System – OTIS); and

-

In at least one region, a weekly report to the region, listing every segregated inmate.

77 Ministry staff acknowledge that the segregation data is flawed. We reviewed numerous internal emails where Ministry staff questioned the accuracy and completeness of information provided by correctional facilities. Commonly, the daily count of segregated inmates does not match the information in OTIS or the 30-day reports sent to regional Ministry offices. One email we reviewed included statistical information, with the caveat that “[a]s always, segregation start dates, and in turn, segregation lengths are questionable.” Another email noted that the data “contained in OTIS is far from perfect so we have major discrepancies in start dates, length, placement…and it is not matching at all.”

78 Others we interviewed made similar observations about issues with segregation data entered at the institutional level. As one employee put it, there are “so many opportunities for error…sometimes mistakes are just made and they get carried forward and I am not sure at what point they even get caught.”

79 Some of these problems can be attributed to confusion about what comes within the definition of “segregation” and what qualifies as a break in a segregation placement. A clearer definition of segregation and guidance about what constitutes a break should eliminate this problem. However, even with clear definitions, the manual nature of data entry – especially when that data must be entered multiple ways in multiple places – increases the risk of human error.

80 In one example we discovered, Central North Correctional Centre (CNCC) staff wrongly recorded segregation start dates in daily count reports as “month/day” instead of “day/month” – so November 3 (3/11) was recorded as March 11. At first, the Ministry wasn’t sure whether CNCC had made a mistake or whether there was another explanation, but one employee noted in an email, “CNCC regularly does the date format wrong. We are going to have to confirm these are the REAL dates.”

81 Errors can also occur when an inmate’s placement is not updated in the computer system (OTIS) in a timely manner. We were told that at one facility, admission and discharge officers are responsible for updating inmates’ placement in OTIS when they are moved. However, these officers are sometimes not notified when an inmate is moved into a segregation cell, so the system isn’t updated, and this results in errors in the facility’s daily reports to the Ministry, because they are based on OTIS information. In this way, one small error can compound and prevent accurate tracking of segregation placements. As one correctional employee told us in an interview, it’s these “little human errors that are important.”

82 Even at facilities where admission and discharge officers aren’t responsible for recording all inmate movements, the same problem emerged. Correctional staff told us it can be difficult to enter inmate placements into OTIS when they change because frontline staff do not have consistent access to computers. Instead, this information may be entered when staff have a “down moment,” often at the beginning or end of a shift. In some facilities, inmate placements are not updated in OTIS over the weekend because of staffing issues. The Ministry should ensure that correctional staff have sufficient resources, including access to computers and time during their shifts, to record changes in an inmate’s placement as they occur, or as soon as practicable.

Recommendation 8

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should ensure that correctional staff have sufficient resources, including access to computers and time during their shifts, to record changes in an inmate’s placement as they occur or as soon as practicable.

83 The Ministry should also research technological solutions that would streamline or automate tracking inmate movement and reduce the possibility of human error. One regional director we spoke with suggested that wristbands or profile cards with barcodes would allow correctional staff to quickly update an inmate’s location when necessary. We also heard that computer tablets could be an efficient and practical way for correctional staff to update information in OTIS. Correctional systems in other jurisdictions might be able to provide the Ministry with best practices related to these new technologies. For example, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety ran a pilot project from 2012 to 2013 to track segregated inmates using tablets and QR codes. According to the report, this project:

…exceeded all the original design criteria set for it, was implemented in a quick, efficient, cost effective manner, and laid the foundation for future technological improvements within the North Carolina prison system...It has had a beneficial impact on inmates, officers and administrators alike.[39].

Recommendation 9

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should research technological solutions that would streamline or automate tracking inmate movement and reduce the possibility of human error, with the goal of implementing a solution within the next 12 months.

84 The Ministry should also implement other mechanisms to ensure employees are recording accurate information about segregation placements and reduce the risk of human error. It should develop policies and provide training on accurately and consistently recording segregation tracking information. The training should emphasize the importance of capturing accurate information and explain how it is used by corrections managers and senior Ministry staff during segregation reviews. As one Ministry official we spoke to recognized:

"[W]e need to train people properly…we need to make it part of the culture that it is not just data recording, it’s not just stats, but that tracking these people’s experiences are important and they matter."

85 The Ministry should also review its various methods for manually capturing segregation data and, where possible, eliminate duplication. This would further reduce the possibility of errors in data entry and allow frontline staff to devote their limited time to other tasks.

Recommendation 10

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should develop policies and provide training on how to accurately and consistently record information necessary to track segregation placements. The training should emphasize the importance of this information and explain how it is used by corrections managers and senior Ministry staff during segregation reviews.

Recommendation 11

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should review its existing methods for capturing segregation data and, where possible, eliminate duplication.

86 The Ministry has been confounded in its attempts to accurately count inmates’ continuous time in segregation when they are moved from one correctional facility to another. According to our interviews, this is how the case of inmate Adam Capay fell through the cracks and escaped scrutiny for so many years.

87 Our Office first began looking into this issue in late 2015, when Alex, an inmate at South West Detention Centre, contacted our Office to complain about his lengthy segregation placement. He asked for our help, saying he felt spending more than two years in continuous segregation was dehumanizing.

88 According to Alex’s housing history, he was first placed in segregation in 2013 after he was accused of a serious offence while in custody. By the time our Office got involved, he had moved between several facilities, including Elgin-Middlesex Detention Centre, Niagara Detention Centre, Central North Correctional Centre, Maplehurst Correctional Complex, and Hamilton-Wentworth Detention Centre. He arrived at South West Detention Centre on September 15, 2015.

89 We were told Alex was held in segregation continuously throughout this time. However, the initial report completed by South West Detention Centre listed September 15, 2015 – the date he arrived there – as the start date of his segregation. The two years he had already spent in segregation were obliterated with this data entry.

90 Subsequent segregation reporting for Alex was based on the September 2015 placement date, and as a result, the 5- and 30-day segregation reports did not reflect that he had been in segregation for more than two years.

91 In February 2016, our Office spoke to the Ministry about these concerns. We were told that it seemed to be “hit and miss” whether time spent in segregation at one facility was counted when an inmate moved to another.

92 In October and November 2016, as part of its review of inmates in long-term segregation, the Ministry attempted to confirm the amount of time Alex had spent in segregation. It noted that based on the September 15, 2015 start date recorded by PESAR – the date Alex was transferred to South West Detention Centre – he had been in segregation for 407 days. However, after further review, his real placement date was revealed – November 2, 2013, meaning he had been segregated (at several different facilities) for 1,098 days.

93 Even now, the Ministry remains unsure how much time Alex really spent in segregation. There are indications in OTIS that he might have been removed from segregation from April to June 2014, but given the unreliability of the data in the system, the Ministry cannot verify whether this placement actually occurred or whether an employee entered something incorrectly.

94 Correctional staff told us about the difficulties they have in determining whether a newly transferred inmate was previously housed in a segregation unit. OTIS might contain institutional unit and cell numbers specific to a particular facility, indicating that an inmate is segregated – but this information has little to no meaning for other facilities, which have their own unit and cell classifications. Further, even if staff take steps to contact a transferring facility and obtain information about an inmate’s previous segregation placement, there is no process to ensure that future segregation reviews are based on the continuous time the inmate has spent in segregation.

95 When we first asked whether the Ministry was tracking segregation placements that spanned multiple correctional facilities, we were told there isn’t a report that regularly looks at transfers across the province. We have since been briefed on a new initiative – the electronic “Care in Placement” tool and the “Active Segregation Report,” discussed later in this report – which might be able to provide this information in future. I am hopeful this new report will solve many of the issues with the existing tracking system. But whatever tool is developed, it is vital that the Ministry accurately record segregation placements across correctional facilities. Without this information, Ministry and correctional staff cannot appropriately review these placements. Once a new tracking method is implemented, staff should receive training on the new procedure and the Ministry should revise its policy to reflect the revised practice.

Recommendation 12

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should develop a standard method to accurately track the total number of consecutive days that an inmate spends in segregation for inmates who are transferred between correctional facilities. Staff should receive training on the new procedure and the Ministry should revise its policy to reflect the revised practice.

96 Given the Ministry’s challenges around data integrity, it has had difficulty quickly and reliably responding to requests for segregation-related statistics. When the Ontario Human Rights Commission asked the Ministry for them, the Ministry initially reported that 939 days was Ontario’s longest continuous segregation placement. As we all now know, this was incorrect; Adam Capay had been continuously in segregation for more than 1,500 days.

97 After that case emerged, and knowing that it couldn’t trust its own data, the Ministry dispatched staff to collect information on inmates who had been in segregation for longer than 365 days as of November 1, 2016.

98 The Ministry is well aware of the limitations in its data. As one employee said in an email we reviewed: “Multiple data sources and inconsistent reporting practices lead to significant data integrity issues, reducing confidence in the [statistical] information we need to provide.”

99 Another related, persistent problem we discovered was the Ministry’s difficulty in reporting on inmates who spend 60 days in segregation over a 12-month period – not continuously, but combined. Since September 2015, Ministry policy has required that in these circumstances, correctional facilities send regional and senior Ministry staff reports setting out whether an inmate has a mental illness or other Human Rights Code-related need that may cause them to be adversely impacted by segregation, as well as information about the reasons for the placement, alternatives considered, and attempts to reintegrate the inmate. However, most of the correctional staff we spoke with were unaware of this policy requirement. One Ministry employee confided to us that “there hasn’t been a [60-day] report generated to date…we can’t figure out how to do it.”

100 After that interview, however, the Ministry provided us with emails from late December 2016 in which it acknowledged the importance of producing these 60-day reports. Shortly after, PESAR started generating a list of inmates who have spent more than 60 aggregate days in segregation. But this list did not specify whether the inmates had Code-related needs, nor did it detail the reasons for continued segregation and any alternatives considered. We understand that the Ministry’s “Active Segregation Report” may eventually have this functionality. As it revises its tracking and reporting procedures, the Ministry should ensure it has a method for tracking and reporting on inmates who spend an aggregate of 60 days in segregation over a 365-day period.

Recommendation 13

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should ensure that it has a standardized method for accurately tracking and reporting on inmates who spend 60 days in segregation over a 365-day period.

101 During our investigation, the Ministry introduced a new process for documenting and reporting on segregation placements across the province. Under this revised process, correctional staff use a tool in the computer system (OTIS) entitled “Care in Placement,” to record when an inmate is placed in segregation and for what reason. According to the Ministry:

"The purpose of implementing the [Care in Placement tool] is to eliminate manual reporting, automate segregation tracking, and reduce the workload on operations and staff responsible for this tracking."

102 The Care in Placement tool – or “screen,” as staff call it – allows users to enter information about the type of segregation placement (close confinement or administrative segregation), its start and end date, who authorized it, and the reason for the placement. The tool maintains a list of every segregation placement for the inmate. Users can manually enter a date for when the next 5- or 30-day review must be completed, but the program does not calculate this date itself or generate an alert for correctional staff. We have been told that this functionality may be added in the future.

Figure 3: Example of the "Care in Placement" tool in the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS), now in use for tracking segregation placements.

103 The Ministry told us Care in Placement data can be exported from OTIS and should be able to generate accurate, timely segregation statistics. It may eventually eliminate some other tracking and reporting requirements for segregation placements, although this has not yet occurred.

104 However, this is not a new feature in OTIS; in fact, it has been available since at least 2002, and was substantially revised in 2004. It was always intended to track segregation placements, but simply was not being used by correctional facilities. We were told that that correctional staff have received training on the Care in Placement tool for years, but the data in OTIS indicates that employees rarely used it, if ever. When asked why the screen wasn’t used by correctional staff, those we interviewed could not provide an explanation. Employees did say they were optimistic about its renewed use, however, with one noting that it meant they were “getting into the ’90s at least.”

105 The Ministry has long been aware of the capabilities of the Care in Placement tool. In a 2015 compliance review of segregation reporting, its Correctional Services Oversight and Investigations unit noted that the tool was “capable of tracking the amount of time an inmate spends in segregation, but is rarely, if ever, used.” It recommended the Ministry explore using this tool to track segregation placements.

106 This recommendation finally gained traction in September 2016, when the Ministry chose to revive the Care in Placement screen to improve segregation tracking. Although the rollout for this initiative was originally targeted for March 31, 2017, project timelines were compressed. Instead of a four-week pilot as originally planned, the Care in Placement screen was only tested briefly; four correctional facilities used it during a two-week pilot in December 2016. When we asked about this compressed timeline, we were told that the Deputy Minister’s office considered the initiative a priority, given the Ministry’s inability to produce timely, accurate data.

107 During the two-week pilot, PESAR staff compared the information entered in the Care in Placement tool to the information provided by facilities in their daily segregation count reports. It found only 77% of segregation placements were documented correctly in both places. Despite this, all correctional facilities began using the tool on January 9, 2017.

108 Unfortunately, the short timeline meant the Ministry did not have time to address concerns identified by the correctional staff who participated in the pilot project. According to a PESAR report on the project, users felt the Care in Placement screen lacked necessary functionality, such as the ability to determine which segregation placements require review and automatically alert staff. Our investigators received the same feedback from correctional staff, who said that facilities must instead come up with their own ways to keep track of which reviews need to be completed each day. One facility we visited had created an elaborate Excel document, while another developed its own program (dubbed “SegTracker”) using an Access database. These workarounds shouldn’t be necessary – the Care in Placement tool, or another Ministry approved program, should be able to calculate and auto-populate the review dates for each segregated inmate.

109 The impact of this missing functionality is threefold: It creates additional work for facilities that must use multiple tools to track and review segregation placement, increases the risk that review dates will be wrongly calculated, and/or that reviews will be missed entirely. The Ministry has been aware of the need for this type of system for more than a year; the same report that recommended the use of the Care in Placement screen also recommended that:

"Institutions should leverage all available scheduling options including Microsoft Office calendars, daytimers or Tickler systems (date-labelled folders) to ensure segregation reviews are not missed."

110 Rather than requiring each facility to develop its own tracking system, the Ministry should increase the functionality of the Care in Placement tool so that it automatically calculates when segregation reviews need to be completed for each inmate. This system should provide staff with automated notifications of these reviews. The Ministry should ensure that it also tracks an inmate’s cumulative time in segregation and alerts staff to the need to review placements.

Recommendation 14

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should increase the functionality of the OTIS Care in Placement tool so that it automatically calculates when segregation reviews need to be completed for each inmate.

Recommendation 15

The computer system (OTIS) should provide frontline correctional staff and facility managers with automated notifications of any reviews that must be completed.

111 Correctional staff told us it is generally not possible to enter data in real-time due to resource limitations; most correctional staff do not have consistent access to a computer. When speaking with PESAR staff about the Care in Placement screen, many expressed confusion over who was responsible for entering Care in Placement data and whether they must do this as placements occur. Although a basic training guide exists, the Ministry should also develop policies regarding the use of the Care in Placement tool to ensure that frontline staff know who is responsible for inputting data and when this must be completed. (According to an internal decision note we reviewed, the Ministry originally intended to develop this type of policy before rolling out the Care in Placement screen, but could not do so when the timeline for the project was compressed.) In addition, the Ministry should ensure that staff have sufficient resources – access to computers and time during their shift – to enter the information in OTIS.

Recommendation 16

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should develop policies regarding the use of the Care in Placement tool to ensure frontline staff know who is responsible for inputting data and when this must be completed. The Ministry should also ensure that staff have sufficient resources – access to computers and time during their shift – to enter the information in OTIS.

112 The Care in Placement tool appears to have promise, but its usefulness will depend on the consistency of its use and the accuracy of data entered by corrections staff. The Ministry acknowledges that data integrity has been an issue, and enhanced software will only go so far in resolving this problem. There is a need for enhanced oversight to guarantee consistency in the application of the Ministry’s policies and procedures. The Ministry should ensure segregation information is rigorously audited and compared to other sources of segregation data in order to make certain that it is reliable and accurate.

Recommendation 17

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should regularly audit the data entered in the OTIS Care in Placement tool to ensure its accuracy and integrity.

113 In my submission to the Ministry in May, I recommended that it:

"…regularly generate and proactively review reports that provide details of all segregation placements in the province to ensure that each placement is in accordance with segregation requirements and then take appropriate remedial steps, as warranted"[40].

114 In a subsequent presentation to my Office, a member of the Deputy Minister’s staff said data from the Care in Placement tool in OTIS will be used to populate an “Active Segregation Report” that will theoretically allow for robust tracking of all segregation placements, including aggregate placements and continuous placements between facilities. We were told the report will also extract data from other parts of OTIS, as well as other electronic documents maintained by the Ministry. The Ministry said this will allow it to generate “exception reports,” which will help identify data entry errors in OTIS.

115 We were told that, at present, the Active Segregation Report can only be viewed by members of the working group that developed the report, and PESAR staff, although the Ministry says it intends to provide broader access in the future. To ensure that frontline segregation staff and corrections managers can spot and address problems proactively, they should also be given access, on an expedited basis, to view portions of the Active Segregation Report and exception reports related to their facility. The Ministry should provide training to them about how to use and interpret the report.

Recommendation 18

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should, on an expedited basis, give frontline staff and corrections managers access to view portions of the Active Segregation Report and exception reports related to their facility. The Ministry should provide training to these individuals about how to use and interpret the report.

116 As I noted in my May submission to the Ministry, information about the use of segregation is of significant public interest and is necessary for the public to hold the government accountable for its actions. I made several recommendations regarding how this data should be collected and reported, and am reiterating these recommendations based on our findings in this investigation.

117 In recent years, the government has recognized the importance of sharing all types of data with the public and committed to making Ontario’s data open by default[41]. It has already published hundreds of datasets and is in the process of making hundreds more publicly accessible, with the intent of increasing transparency and accountability and encouraging innovation and problem solving.

118 Making anonymized segregation data available to the public would ensure that inmates in long-term segregation – including Adam Capay – could not languish in segregation year after year without the knowledge of the public or the Ministry. Public reporting of statistics on the use of segregation will enhance transparency and accountability and allow for more effective oversight of segregation placements. The Care in Placement/Active Segregation Report data should be anonymized and reported publicly.

119 At present, the Active Segregation Report – and the Ministry’s other data collection analytics and management reforms – are managed by an ad hoc group of Ministry staff who have had their other work put on hold for this project. Given the importance of timely and accurate segregation statistics, the Ministry should create a permanent team to continue this work and ensure it is sufficiently resourced. This permanent team should be included in any discussions about policy changes that could affect segregation data collection or statistical reporting.

120 Given the profound consequences that isolation can have on an inmate’s health and well-being, the Ministry should ensure it collects, analyzes, and reports on whether segregated inmates have mental health issues, developmental disabilities, or other Human Rights Code-related needs, as well as the date the inmate last met with a health care professional and whether there is a care and/or treatment plan. This information is already being captured by the Ministry, and including it in the Active Segregation Report would allow for greater oversight of segregation placements for vulnerable inmates.

121 The Ministry should also keep and report annually on statistics about the use of segregation across facilities and amongst various inmate populations. This should include information about the inmate’s gender, race, mental health status, aboriginal status, and other relevant personal factors, as well as instances of self-harm, increased medical treatment, hospitalization, and deaths occurring during segregation. Tracking and monitoring this information would help the Ministry understand the use and impact of segregation amongst various inmate populations.

Recommendation 19

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should make segregation data available to the public in an anonymized form on an ongoing basis as part of the province’s open data initiative.

Recommendation 20

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should create a permanent data management and reporting team and ensure it is sufficiently resourced. This team should be included in discussions about policy changes that could affect segregation data collection or statistical reporting.

Recommendation 21

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services should collect information on:

- whether segregated inmates have mental health or developmental disabilities or other Human Rights Code-related needs.