Enquête sur les directives données par le ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels aux services de police de l’Ontario sur la désescalade des situations conflictuelles

« Une question de vie ou de mort »

Paul Dubé

Ombudsman de l'Ontario

juin 2016

Bureau de l'Ombudsman de l'Ontario

Nous sommes

Un bureau indépendant de l'Assemblée législative qui examine et règle les plaintes du public à propos des services fournis par les organismes du secteur public de l'Ontario. Ces organismes comprennent les ministères, les agences, les conseils, les commissions, les sociétés et les tribunaux du gouvernement provincial, ainsi que les municipalitiés, les universités, les conseils scolaires, les services de la protection de l'enfance et les services en français. L'Ombudsman recommande des solutions aux problèmes administratifs individuels et systémiques.

Nos valeurs

Traitement équitable

Administration responsable

Indépendence, impartialité

Résultats : accomplir de réels changements

Notre mission

Nous nous efforçons de jouer le rôle d’un agent de changement positif, en favorisant l’équité, la responsabilisation et la transparence du secteur public, et en promouvant le respect des droits aux services en français ainsi que des droits des enfants et des jeunes.

Notre vision

Un secteur public oeuvrant au service des citoyens, dans l’équité, la responsabilisation, la transparence et le respect des droits.

Contributeur(trice)s

Directeur, Équipe d’intervention speciale de l’Ombudsman

Enquêteurs principaux

- Ronan O'Leary

- Adam Orfanakos

Enquêteur(euse)s

- William Cutbush

- Domonie Pierre

Agent de règlement préventif

Conférence de presse :

Table des matières

- Résumé analytique

- Processus d'enquête

- Les coûts humains

- En quête de changement : 25 ans d'appel à l’action

- Lester Donaldson – Toronto, 1988 (enquête de 1994)

- Edmond Yu – Toronto, 1997 (enquête de 1999)

- Otto Vass – Toronto, 2000 (enquête de 2006)

- O’Brien Christopher-Reid – Toronto, 2004 (enquête de 2007)

- Byron Richard Debassige – Toronto, 2008 (enquête de 2010)

- Douglas Minty et Levi Schaeffer – OPP, 2009 (enquêtes de 2014, 2011)

- Aron Firman – OPP, 2010 (enquête de 2013)

- Evan Jones – Brantford, 2010 (enquête de 2012)

- Steven Mesic – Hamilton, 2013 (enquête de 2014)

- Michael Eligon, fils – Toronto, 2012 (enquête de 2014)

- Évolution de la désescalade : La roue tourne

- Qui est responsable ? Rôle du ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels

- Intensifier les efforts : Améliorer la formation à la désescalade pour les policiers partout en Ontario

- « La loi des policiers » : Changer la culture des milieux policiers

- Conclusion

- Recommandations

- Réponse

- Annexe : Réponse du Ministere de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels

1 Le 27 juillet 2013, Sammy Yatim, âgé de 18 ans, a été tué par balles par un membre du Service de police de Toronto. Le jeune homme se trouvait alors seul dans un tramway de Toronto, et tenait un petit couteau. La scène a été captée sur vidéo et diffusée dans les médias sociaux, suscitant de vives inquiétudes parmi le public qui se demandait quand, pourquoi et comment les policiers de l’Ontario avaient recours à la force mortelle.

2 Cette affaire s’est avérée inhabituelle à deux égards seulement : premièrement, la puissance dramatique de ses images vidéo – vues un demi-million de fois durant les quatre premiers jours – a fait d'elle un incident réel et immédiat aux yeux d'un vaste public. Deuxièmement, l’un des policiers impliqués a été accusé de meurtre au second degré et de tentative de meurtre[1] – fait extrêmement rare en Ontario, où les policiers sont presque toujours innocentés dans pareils cas, car leurs actes sont considérés comme un recours à une force raisonnable.

3 Sur tous les autres plans, la mort de Sammy Yatim était tristement familière, rappelant de trop nombreux incidents similaires, au fil de trop nombreuses années. Son décès présentait des similarités presque inquiétantes avec un incident survenu 16 ans plus tôt, en 1997, où la Police de Toronto avait abattu par balles Edmond Yu, 35 ans, alors qu’il brandissait un petit marteau, seul dans un autobus. Comme M. Yatim, M. Yu était en crise. Tout comme beaucoup d’autres aussi, dont :

-

Byron Debassige, 28 ans, qui avait volé des citrons et était armé d’un couteau long de trois pouces quand il a été tué par la Police de Toronto en février 2008.

-

Douglas Minty, 59 ans, qui était armé d’un couteau de poche quand il a été tué par la Police provinciale de l’Ontario à Elmvale en juin 2009.

-

Michael Eligon, 29 ans, qui portait encore la tenue d’hôpital dont il était vêtu quand il s’était échappé de cet établissement et qui avait deux paires de ciseaux, quand il a été tué par la Police de Toronto en février 2012.

-

Michael MacIsaac, 47 ans, qui courait dans la rue complètement nu, brandissant un pied de table, quand il a été tué par la Police régionale de Durham en décembre 2013.

4 Les nouvelles et les images bouleversantes de l’affaire Yatim ont mobilisé le public. Des centaines de personnes ont participé à des manifestations de protestation en son honneur, durant lesquelles certains ont dit de lui qu'il était « le fils de tout le monde ». Lors de ces événements, d’autres familles frappées par de nombreuses tragédies précédentes se sont jointes à sa parenté. Ensemble, elles ont ravivé l'intérêt et l'urgence d’une question posée de longue date sur le comportement et la formation des policiers : lors d'interventions, la police faisait-elle suffisamment pour essayer de calmer les gens par des paroles et éviter ainsi d’avoir à faire feu sur eux?

5 Cette enquête a été ouverte pour tenter de répondre à cette question. La formation des policiers relève en fin de compte de la responsabilité du gouvernement de l’Ontario, et il est de l’intérêt public d’examiner quelles directives il donne, ou non, à la police pour l’inciter à désamorcer de telles situations et pour éviter si possible l'usage d'une force mortelle. Pour cela, nos enquêteurs ont étudié la documentation de décès causés par la police en Ontario, les lignes directrices et les directives provinciales sur l'usage de la force et la formation des policiers, ainsi que les théories et les pratiques exemplaires de la désescalade au Canada et à l’étranger.

6 Il y a eu de nombreuses fusillades policières mortelles en Ontario, dont les victimes étaient des personnes atteintes de maladie mentale, au cours des dernières années – plus de 40 rien que depuis 2000. Elles ont déclenché de multiples enquêtes et études. Depuis 1989, les enquêtes du coroner se sont soldées par plus de 550 recommandations en vue d’améliorations et de changements. À la suite du tir mortel dont Sammy Yatim a été victime, Frank Iacobucci, ancien juge de la Cour suprême maintenant à la retraite, a publié un rapport et des recommandations pour le Service de police de Toronto[2]. Quant au ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels de l’Ontario, qui a légalement la responsabilité du maintien de l’ordre en vertu de la Loi sur les services policiers, il a entrepris une étude sur les interactions entre les policiers et les personnes atteintes de maladie mentale, un an avant le décès de Sammy Yatim, mais cette étude a produit peu de résultats plus de quatre ans après.

7 Depuis près de trois décennies, ces rapports et recommandations soulignent encore et toujours l’importance, pour les policiers, de recourir à des techniques de désescalade face à des gens en crise. Ils préconisent de simples directives, par exemple offrir calmement une aide, au lieu de hurler des ordres après avoir dégainé leurs armes. Pourtant, bien peu de mesures concrètes ont été prises en ce sens.

8 Notre enquête a révélé que les policiers en Ontario reçoivent beaucoup de formation sur la manière d'utiliser leur pistolet, mais pas assez sur celle d'utiliser les mots. Leur formation sur « l’usage de la force » porte principalement sur l’utilisation des armes, et très peu sur les moyens verbaux qui peuvent les aider à calmer une personne armée, en situation de crise.

9 Le problème, ce n’est pas que les policiers ne suivent pas leur formation. Ils la suivent. Le problème est la formation elle-même. Les policiers apprennent que, quand ils se trouvent confrontés à quelqu’un muni d’un couteau, ils doivent dégainer leur pistolet et ordonner d’une voix forte à cette personne de déposer son arme. Certes, cette tactique peut s’avérer efficace avec des gens rationnels, mais quelqu'un qui brandit une arme face à des policiers armés est irrationnel, par définition. Trop souvent, l’ordre lancé par les policiers ne fait qu'aggraver la situation. Il peut exacerber l'état mental de la personne qui se comporte déjà irrationnellement, et qui se trouve en crise. De plus, une fois que les policiers ont dégainé leur pistolet, bien souvent, la seule tactique qui leur reste est d'utiliser leur arme.

10 Notre enquête a mis en évidence des problèmes en ce qui concerne le type et l’étendue de la formation que reçoivent les policiers en Ontario. Les agents de police n'ont que 12 semaines de formation de base, soit beaucoup moins que leurs homologues ailleurs au Canada. Les techniques de désescalade et de communication ne sont explicitement abordées que durant cinq séances de 90 minutes. L’examen de passage final sur le recours à la force porte principalement sur l’usage de la force et non pas sur celui du jugement pour désamorcer une situation. Par la suite, la formation des policiers est laissée à la discrétion de leurs services de police respectifs et la province ne fait aucun contrôle pour veiller à l'uniformité de cette formation entre les différents services.

11 Dans tout service de police, les policiers sont tenus de suivre une formation annuelle de renouvellement de la certification sur l’usage des armes à feu et des matraques, mais il n’y a rien d’équivalent pour les compétences de désescalade qu’ils peuvent utiliser chaque jour dans leur profession. Chaque année, ils suivent un cours de « mise à jour » sur le recours à la force, d'une durée d'un jour, mais il appartient à chaque service de police de décider si ce cours comprend un volet sur la désescalade ou non.

12 Tout le problème plus vaste de la culture du milieu policier amplifie ces lacunes du programme de formation. Comme la formation à la désescalade est restreinte au Collège de police de l'Ontario, et discrétionnaire au sein des services de police, elle ne peut en rien contrer une culture qui, dans certains milieux policiers, perpétue la notion que les fusillades mortelles sont tout simplement inévitables dans le cas de personnes atteintes de maladie mentale.

13 Le ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels a le pouvoir, la possibilité et le devoir d'aborder ces problèmes de front. Mais jusqu’à présent, il s’est surtout contenté d'un laisser-faire. Il n’a même pas défini le sens de la « désescalade », et encore moins cerné clairement ses attentes envers nos services de police. Alors qu'il gère le Collège de police de l’Ontario, il n’a rien fait pour renforcer la formation à la désescalade dans cet établissement, ni pour exiger une formation plus poussée à la désescalade pour les policiers déjà en exercice.

14 La seule mesure concrète prise par le Ministère dans ce domaine a été d’élargir l’usage des armes à impulsions – c’est-à-dire des Tasers. Bien qu’ils puissent se substituer à l'usage de la force mortelle dans de rares circonstances, les Tasers restent des armes, et n’ont rien à voir avec les tactiques de désescalade. Alors que dans d’autres instances au Canada, et ailleurs dans le monde, des progrès sont accomplis dans la mise en place de nouvelles techniques policières, l’Ontario néglige la formation à la désescalade, allant même jusqu’à la réduire, par souci d’économies. Pourtant, les coûts des enquêtes, des examens de l’Unité des enquêtes spéciales (UES) et de toutes les procédures judiciaires qui peuvent résulter de fusillades policières ne font qu'augmenter. Sans parler des coûts en termes humains, non seulement pour les victimes, mais aussi pour les policiers impliqués dans ces événements traumatiques, et pour tous leurs proches.

15 Bon nombre des examens précédents à ce sujet, dont le rapport publié par le juge Iacobucci en 2014, ont porté sur des décès survenus à Toronto et causés par la police de la ville. Mais le problème n'est pas que torontois. C’est un problème ontarien, qui exige une intervention à l’échelle provinciale, avant que d’autres personnes ne perdent regrettablement la vie. Le gouvernement provincial doit assumer sa responsabilité légale et indiquer comment les services de police doivent réagir avec les personnes atteintes de maladie mentale, ou qui se trouvent en situation de crise pour toute autre raison.

16 Ce rapport présente 22 recommandations au ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels, axées aussi bien sur ses directives et ses modèles législatifs que sur la formation des policiers à tous les niveaux, en passant par un meilleur suivi et de meilleures évaluations des interventions policières dans le cas de personnes en crise.

17 L’objectif de ces recommandations, sur un plan systémique, n'est pas simplement d'élargir la formation, mais de parvenir à un changement de culture dans les milieux policiers. Nous faisons confiance aux policiers pour qu’ils s’en remettent à leur jugement dans des situations dangereuses, afin de protéger nos vies et la leur. Ils devraient avoir de meilleurs outils pour réagir face à des personnes en crise, pour mieux déterminer quand utiliser la force et quand recourir à la désescalade, afin de préserver des vies.

18 L’attention portée par le public aux décès causés par la police n’a fait que croître depuis la mort de Sammy Yatim, comme nous l’avons vu partout aux États-Unis, de Ferguson, dans le Missouri jusqu’à la ville de New York, en passant par North Charleston, en Caroline du Sud, et ici chez nous. Depuis, il y a eu 35 fusillades policières en Ontario, dont 18 ont été mortelles. L’une d’elles – dont a été victime Andrew Loku, 45 ans, qui tenait un marteau quand la Police de Toronto l’a tué par balles dans le couloir de son immeuble d’habitation en juillet 2015 – a provoqué plusieurs semaines de manifestations et des appels à plus de transparence concernant les enquêtes de l’UES, qui n’a alors porté aucune accusation[3]. Cette affaire fera l’objet d’une autre enquête encore, annoncée en avril 2016[4].

19 Le gouvernement a donné la preuve qu’il souhaite et peut réagir aux vives inquiétudes du public au sujet des services policiers et de leur culture, et imposer des règles à l’échelle de la province dans l’intérêt du public. Il l’a fait en 1992, avec sa directive d’origine sur le recours à la force. Il l’a fait aussi en 1999 pour mettre fin aux poursuites policières à grande vitesse qui sont dangereuses. Et l’an dernier, le Ministère a non seulement tenu plusieurs consultations publiques sur le processus controversé de vérifications ciblées, ou « fichage » – mais il a aussi ébauché un nouveau Règlement (que le gouvernement a adopté) en quelques mois seulement. Le temps est venu de régler le problème de la désescalade des conflits – et tout particulièrement des lacunes de formation et des questions de culture qui ont fait que trop de policiers étaient mal préparés pour recourir à des techniques de désescalade, causant trop de pertes de vies. C’est littéralement une question de vie ou de mort.

20 Immédiatement après la mort de Sammy Yatim, tué par balles le 27 juillet 2013, l’Unité des enquêtes spéciales de l'Ontario a ouvert une enquête, des vidéos de témoins de l'incident ont été consultées des milliers de fois sur YouTube, et des débats publics ont fait rage sur le comment et le pourquoi de telles tragédies.

21 Quatre jours plus tard, le 31 juillet 2013, mon Bureau a annoncé que l’Ombudsman ferait une évaluation de cas – étape précédant une enquête – pour voir comment les policiers sont formés à désamorcer les situations conflictuelles avant de recourir à la force mortelle. Les enquêteurs ont examiné l’orientation et les directives données à la police par le ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels. Ils ont aussi cherché à déterminer si le Ministère devrait faire valoir son autorité pour imposer des normes provinciales relativement à cette formation[5].

22 Cette évaluation a inclus un examen préliminaire des directives provinciales, des méthodes et de la formation des policiers, ainsi que l’étude de cas similaires à celui de Sammy Yatim en Ontario et ailleurs. Elle a étudié les recommandations faites dans le cadre de nombreuses enquêtes du coroner à propos de décès similaires, et la situation dans d’autres instances, par exemple en Colombie-Britannique, où le gouvernement provincial a imposé des normes de formation à la désescalade pour les policiers, à la suite du décès de Robert Dziekanski lors d'une intervention policière à l’aéroport de Vancouver en 2007.

23 Le Ministère a été avisé le 7 août 2013, et l’enquête publique a été annoncée le lendemain[6]. À cette époque, notre Bureau avait déjà reçu 60 plaintes, présentations et demandes de renseignements de nombreux citoyens préoccupés, appartenant à divers milieux, entre autres au secteur de l'exécution de la loi. Au total, nous avons reçu 176 plaintes et présentations dans le cadre de cette enquête.

24 Une équipe composée de trois enquêteurs de l’EISO, d'un agent de règlement préventif et d'une conseillère juridique a été affectée à cette enquête, avec l’appui du directeur de l’EISO, au besoin. En outre, deux anciens chefs de police émérites ont été invités à titre de conseillers spéciaux : le sénateur Vern White, ancien chef du Service de police d’Ottawa, du Service de la police régionale de Durham, et ancien commissaire adjoint de la Gendarmerie royale du Canada, et Mike Boyd, ancien chef du Service de police d’Edmonton, et ancien chef adjoint et chef intérimaire du Service de police de Toronto. Tous deux ont généreusement répondu à mon appel et offert leurs services bénévolement. Ils nous ont fait part de leurs connaissances et de leurs conseils sur les pratiques exemplaires, nous apportant un soutien précieux dans l’élaboration des recommandations.

25 L’équipe a effectué 95 entrevues, notamment avec des instructeurs du Collège de police de l’Ontario et des fonctionnaires de la Section des normes policières et de l’Unité des opérations du Ministère, des chefs de police à la retraite, des formateurs chargés d'enseigner l'usage de la force, des universitaires ayant la connaissance des services policiers, des psychiatres et des psychologues habitués au règlement des crises et à la formation des policiers, des groupes d’intérêt, et des organismes de service et de défense dans le domaine de la santé mentale. Elle a aussi parlé avec de la parenté de 13 personnes décédées à la suite d’interventions policières, pour écouter leurs préoccupations et leurs recommandations en vue de changements.

26 Par ailleurs, nos enquêteurs ont parlé à des formateurs de plusieurs services de police en Ontario et ils ont observé des séances de formation au Collège de police de l’Ontario, au Justice Institute of British Columbia, ainsi que dans des services régionaux de police en Ontario.

27 Ils ont également examiné ce que faisaient d’autres instances un peu partout au Canada, aux États-Unis, au Royaume-Uni et en Australie pour voir comment elles traitaient le sujet de la désescalade. Nos enquêteurs ont plus particulièrement communiqué avec des responsables en Colombie-Britannique de l'élaboration et de la prestation de la formation sur l’intervention et la désescalade en situation de crise (IDC), qui est obligatoire dans cette province et qui est la seule formation provinciale standardisée à la désescalade pour les policiers au Canada[7].

28 Notre équipe s’est aussi penchée sur une imposante documentation, dont des documents de formation du Collège de police de l’Ontario qui remontaient jusqu’à 2003, ainsi que du matériel didactique du Réseau canadien du savoir policier[8] et de l’Ontario Police Video Training Alliance. Le Ministère nous a fait parvenir des courriels, des notes de service et des projets de recherche rattachés aux thèmes de notre enquête, ainsi que des rapports d’inspection ministériels sur les 52 services de police municipale et sur la Police provinciale de l’Ontario, relativement à leur respect des exigences de formation.

29 Nous avons aussi consulté diverses études universitaires sur la désescalade des conflits, la formation à l'usage de la force et les réactions des policiers face aux personnes atteintes de maladie mentale. Nos enquêteurs ont participé à des conférences, notamment à celle organisée conjointement par l’Association canadienne des chefs de police et la Commission de la santé mentale du Canada sur le thème des interactions des policiers avec des personnes atteintes de maladie mentale[9].

30 Notre Bureau a bénéficié de l’excellente collaboration du Ministère et du Collège de police de l’Ontario tout au long de cette enquête. Nous avons aussi communiqué avec les organismes suivants : Police Association of Ontario, Ontario Association of Police Educators, Ontario Association of Police Services Boards et Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police. Nous avons obtenu la collaboration de tous, sauf de ce dernier. La coopération du reste de la communauté policière s’est avérée mitigée. Nous avons envoyé 173 lettres aux chefs des services municipaux et régionaux de police, aux commissions de services policiers et aux associations de police, leur demandant leur collaboration et leurs conseils. Nous avons reçu 33 réponses, mais seulement 15 d’entre elles présentaient des renseignements significatifs.

31 Ceci dit, le Service de la police régionale de Durham, le Service de la police régionale de Peel, la Police provinciale de l’Ontario et le Service de police du Grand Sudbury sont à féliciter de leur collaboration, car ils ont notamment permis à nos enquêteurs de consulter leurs plans de leçons, et d’assister à des cours et à des séances de formation.

32 En mars 2015, mon prédécesseur a envoyé une ébauche de ce rapport au Ministère pour obtenir ses commentaires, comme notre Bureau le fait habituellement en vertu de la Loi sur l’ombudsman. Le Ministère nous a répondu en avril 2015, précisant qu’il avait entrepris plusieurs initiatives qui répondraient à nos recommandations, mais que celles-ci en étaient encore « à diverses étapes de développement » – dont la mise en œuvre de sa « Stratégie pour une meilleure sécurité en Ontario » (pour laquelle il a annoncé des consultations publiques en août 2015)[10].

33 Mon prédécesseur a décidé de ne pas mettre la touche finale à ce rapport avant la fin de son mandat, en septembre 2015. Le procès du policier accusé d'avoir causé la mort de Sammy Yatim était alors en cours. Nos enquêteurs ont continué de faire un suivi auprès du Collège de police de l’Ontario et du Ministère en novembre 2015, demandant des renseignements sur toute évolution de la situation. Le Ministère nous a fait parvenir une réponse en avril 2016, disant qu’en dépit de certaines modifications apportées à la formation à la désescalade, aux communications et à la santé mentale, le programme écrit restait inchangé. J’ai été avisé de l'état d'avancement de cette enquête au début d’avril 2016, peu après avoir pris mes fonctions, et j’ai demandé à l’équipe d’enquête d’actualiser au plus vite le rapport pour intégrer tout nouveau renseignement.

34 J’ai rencontré le ministre alors en poste au ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels, Yasir Naqvi, le 18 mai 2016, et j'ai remis une ébauche actualisée de ce rapport, à lui et à son Ministère. Le 3 juin, avec le directeur de l’EISO, l’Ombudsman adjointe et l’enquêteur principal chargé de ce dossier, j’ai rencontré de hauts dirigeants ministériels, qui nous ont présenté leur Stratégie pour une meilleure sécurité en Ontario. Le 10 juin, nous avons reçu la réponse du Ministère aux recommandations de ce rapport. Malheureusement, le Ministère n’a toujours pris aucun engagement significatif pour mettre en œuvre mes recommandations. (Pour plus de détails, voir la partie consacrée à la Réponse et l’Annexe à la fin de ce rapport.)

35 Voici la clarification de certains des termes utilisés dans ce rapport :

36 Usage de la force : Les policiers sont autorisés à utiliser la force, à un degré raisonnable selon la situation, pour empêcher la perpétration de certaines infractions et/ou pour protéger leur vie et celle d’autres. Cette expression fait référence à toute une gamme de tactiques, allant du contrôle physique à l’usage d’armes intermédiaires, jusqu’au recours à la force mortelle.

-

Armes intermédiaires : Cette expression fait référence aux matraques, aux armes à impulsions (plus couramment connues sous le nom de marque Taser, utilisé dans ce rapport) et aux aérosols (brumiseurs d’oléorésine de capsicum, couramment appelé gaz poivré ou O/C).

-

Force mortelle : Cette expression fait référence à des tactiques qui peuvent entraîner de graves lésions corporelles ou la mort; elle signifie le plus souvent l’usage d’armes à feu par les policiers.

37 Désescalade : Lorsque la police est appelée à intervenir, en interaction avec le public, cette expression fait référence au passage d'une situation extrêmement tendue à une situation de tension réduite[11].

38 Sommation de la police : Cette expression fait référence à l’avertissement standard des policiers – « Police! Ne bougez plus! » – qui doit être prononcé à voix forte dans les situations potentiellement mortelles, où les policiers dégainent leurs armes à feu.

39 Personne atteinte de maladie mentale / personne en crise / perturbé affectif : Ces trois termes sont souvent utilisés dans la documentation sur les interventions de la police en situation de crise.

-

Personne atteinte de maladie mentale est l’expression utilisée par l’Association canadienne des chefs de police pour décrire toute personne dont le comportement est influencé par un stress important ou une maladie mentale lors de l'interaction[12].

-

Personne en crise est l’expression privilégiée par le juge Frank Iacobucci dans son rapport de 2014 sur l’affaire Sammy Yatim, ainsi que dans notre rapport. Elle ne s’applique pas uniquement aux personnes atteintes de maladie mentale. Elle fait plutôt référence à la personne en question, à son comportement et à la situation qu'elle vit, sans en présumer les raisons.

-

Perturbé affectif est l’expression très généralement employée par les organismes policiers pour décrire une personne agitée en raison d’une maladie mentale, de stress ou d’autres raisons. Elle est critiquée, entre autres par la Commission ontarienne des droits de la personne[13].

40 Tout juste un an après le décès de Sammy Yatim, notre Bureau a interviewé son père, Nabil (Bill) Yatim. M. Yatim était encore anéanti et profondément peiné par la perte de son fils. Il ne parvenait pas à comprendre comment la police – « des gens qui sont chargés de vous protéger et de vous servir » – pouvait avoir agi ainsi. Il ne pouvait pas s’empêcher de penser que, si les policiers avaient été correctement formés pour réagir face à quelqu’un en crise émotionnelle, Sammy Yatim serait encore en vie :

Ce qu’il fallait ce soir-là [à Sammy], c’était quelqu’un qui l’enroule dans une couverture et le ramène à la maison, pas quelqu’un qui tire sur lui à neuf reprises.

41 Lors de rencontres avec les familles et les amis proches de 13 personnes décédées lors d’interventions similaires de la police, tous ont dit la même chose à notre équipe : l’être qui leur était cher se trouvait en crise et avait besoin d’aide. M. Yatim a reconnu que son fils portait une arme, ce qui avait accru la tension. Mais à son avis, les policiers auraient dû comprendre que le petit couteau serré dans la main de Sammy posait très peu de risques. Ils auraient dû voir que Sammy était en crise émotionnelle et ne répondait pas à leurs ordres. Voici ce qu'il a déclaré :

Une personne en crise ne peut même pas saisir ou comprendre de quoi vous parlez. [Elle] ne peut même pas entendre un simple ordre verbal et le traiter normalement. Ça ne veut pas dire qu’elle désobéit à cet ordre. Ça ne veut pas dire que vous devez vider votre pistolet.

42 Très généralement, ces gens dans la peine ont dit qu’ils avaient bien du mal à comprendre pourquoi les policiers en étaient venus à utiliser une force mortelle, alors qu’ils auraient dû aider. La plupart pensaient que les policiers avaient eu la gâchette trop facile, au lieu de tenter une désescalade de la situation. Beaucoup avaient perdu toute confiance dans la police et dans le rôle qu’elle est censée jouer, qui est de protéger et servir le public, après avoir été témoins d'une mentalité qu'ils ont qualifiée de « nous contre eux » chez les policiers.

43 Leur chagrin et leur frustration les ont aussi menés à poser des questions précises sur le niveau de formation à la désescalade donnée aux policiers. Ils ont demandé : Les policiers sont-ils formés à reconnaître une personne en crise, par opposition à un criminel? Sont-ils formés à essayer d’aider une personne, au lieu de hurler « Jetez votre arme à terre! » en visant la personne avec leur arme à feu?

44 Comme ces familles le savent fort bien, il y a eu trop de cas semblables, trop d’enquêtes du coroner, de recommandations, d’examens et de rapports qui sont toujours restés sans suite, depuis des décennies. Elles ont dit qu’elles étaient venues à nous dans l’espoir d’obtenir des changements durables et réels : obtenir que les policiers prennent pour habitude de chercher à désamorcer une situation en premier quand les gens sont en crise émotionnelle, et évitent au maximum l'usage d'une force mortelle. Leur espoir, c’est qu’aucune autre famille n’ait à souffrir comme elles ont souffert.

45 Il faut aussi souligner que le tribut payé sur le plan humain dans de telles affaires s’étend également à la police. Aucun policier ne commence son quart de travail en s’attendant à tuer quelqu’un. Quand ceci se produit, les victimes et leur famille ne sont pas seules à payer. Les policiers impliqués, et leur famille, souffrent eux aussi de traumatisme[14].

46 Ces familles ne représentaient qu’une toute petite partie de celles touchées par des décès de personnes en crise, survenus au cours d'interventions policières durant les 25 dernières années en Ontario. Habituellement, dans ces cas, il y a une enquête et un jury du coroner fait des recommandations. Notre enquête a examiné les recommandations – des centaines au total – de ces jurys. À maintes reprises, encore et toujours, elles ont préconisé d’améliorer la formation des policiers à la désescalade, mais très peu ont été suivies de mesures d'action. Les résumés ci-après présentent le message des familles qui ont perdu des êtres chers lors d’une interaction mortelle avec des policiers et soulignent le besoin de changements trop longtemps attendus au niveau provincial.

47 M. Donaldson était âgé de 45 ans et il était déjà connu de la Police de Toronto quand des policiers se sont retrouvés face à lui à son domicile en août 1988. Il souffrait de schizophrénie paranoïde et de délires, avait précédemment tenté de poignarder un policier et en avait attaqué un autre avec une pelle. Cette fois, quand il a sorti un couteau, un policier a tiré et l’a abattu.

48 L’enquête du coroner sur son décès ne s’est achevée qu’en 1994, mais les recommandations ont mené à d’importants changements dans les procédures policières et la formation des policiers, entre autres avec la création d'un cours sur la résolution des crises à l'intention des policiers[15]. Selon Saving Lives, rapport de 2002 publié par l’Urban Alliance on Race Relations et le Queen Street Patient’s Council, ce cours a été offert à la Police de Toronto, mais abandonné trois ans plus tard en raison de coupures budgétaires[16].

49 L’une des autres recommandations du jury dans l’enquête sur l’affaire Donaldson était de faire participer des professionnels de la santé mentale et des survivants de la psychiatrie à la formation donnée aux policiers, d'enseigner aux policiers comment réagir face à des personnes en détresse psychologique, et de lutter contre certains stéréotypes et attitudes envers les personnes atteintes de maladie mentale.

50 De plus, dans le sillage de cette enquête, le Collège de police de l’Ontario a conçu un manuel à l’intention des policiers qui ont affaire à des personnes atteintes de maladie mentale[17]. Ce manuel, publié par le Centre de toxicomanie et de santé mentale, est distribué gratuitement à chacun des services de police en Ontario, pour être utilisé dans le cadre de la formation des policiers de première ligne.

51 Avant que les médecins ne diagnostiquent chez lui une schizophrénie paranoïde, M. Yu avait été étudiant en médecine. En février 1997, à l’âge de 35 ans, il avait déjà fait plusieurs séjours en établissement psychiatrique et vécu dans les rues de Toronto, avant de trouver refuge dans une « maison d’hébergement ». La Police de Toronto a été appelée à intervenir, car il avait agressé une femme, en attente à un arrêt d’autobus. Quand les policiers sont arrivés, l’autobus était vide et M. Yu était assis à l’intérieur, à l’arrière.

52 Après quelques échanges avec les policiers, M. Yu est devenu agité, il s’est levé, brandissant un petit marteau d’acier au-dessus de sa tête. Les policiers ont dégainé leur pistolet, et l'ont sommé de ne plus bouger et de jeter son arme à terre. L’un d’eux a fait feu à trois reprises, tuant M. Yu.

53 Le jury du coroner a présenté 24 recommandations, demandant notamment une modification de la Loi sur les services policiers pour exiger que les policiers reçoivent au moins un jour de formation annuelle complémentaire, centrée sur la résolution des crises. Il a souligné qu’inclure cette exigence à la loi garantirait que ce complément de formation est effectivement donné (le jury de l’enquête avait entendu dire qu’aucun des policiers impliqués dans l’affaire Yu n’avait suivi la formation à la résolution des crises brièvement mise en place à la suite de l’enquête sur l’affaire Donaldson). Le jury a aussi recommandé que le cours sur la résolution des crises comprenne, entre autres, les éléments suivants :

-

Désescalade et règlement des situations sans usage de la force physique.

-

Les policiers devraient établir un « premier contact » et suivre la méthode « temps, tactiques, paroles », dans toute la mesure du possible, et « l’écoute active » devrait être une compétence à développer chez eux.

-

Dans toute la mesure du possible, les policiers devraient maintenir une distance de réaction suffisante pour se donner le temps de se désengager, de reprendre tactiquement position et/ou de réagir de sorte à empêcher la situation de passer d’échanges verbaux à des échanges violents.

54 Le rapport Saving Lives a précisé que le Solliciteur général (maintenant devenu le ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels) n’avait pas pris de mesures pour donner suite à la recommandation du jury dans l’affaire Yu, qui préconisait d’inclure une formation à la résolution des crises à la Loi sur les services policiers. Le rapport a souligné ceci : « Les services de police mettent en œuvre une multitude de projets de formation différents qui changent si fréquemment qu’il devient impossible d'assurer un suivi de la performance. »[18] Certes, le Service de police de Toronto avait créé un cours sur la résolution des crises en 1999, qui incluait la désescalade et la résolution des crises[19], mais apparemment, dès 2001, ce cours de 50 heures était intégré à la formation de renouvellement de la certification aux armes à feu[20].

55 M. Vass, 55 ans, marié et père de cinq enfants, avait des antécédents de problèmes de santé mentale et de dépression. En août 2000, des policiers de Toronto sont intervenus alors qu’il avait été blessé lors d’une confrontation avec des adolescents, chez un dépanneur. Les policiers ont tenté de soigner ses blessures, mais quand il est devenu violent, ils l'ont menotté, puis frappé aux jambes avec une matraque. Son décès a été attribué à un stress cardiovasculaire résultant de l’incident.

56 L’Unité des enquêtes spéciales a accusé quatre policiers d’homicide, mais ils ont tous été acquittés. Le jury du coroner a fait 22 recommandations, principalement centrées sur le besoin d'utiliser des Tasers et de former les policiers à l’usage de ces appareils, mais il a aussi préconisé de créer une structure permanente pour discuter de « l’intersection entre les services policiers et les questions relevant du secteur de la santé mentale ».

57 En juin 2004, la Police de Toronto a répondu à plusieurs appels à propos d’un homme qui errait aux alentours d’Edward Gardens, sans chemise, brandissant un couteau. Trois policiers ont abordé M. Christopher-Reid, 26 ans, qui souffrait de délires paranoïdes. Ils ont levé leur pistolet et lui ont ordonné de poser son arme. Mais il a continué d’avancer, et ils l’ont abattu, tirant à quatre reprises.

58 L’Unité des enquêtes spéciales n’a porté aucune accusation. Le jury du coroner chargé de cette affaire a recommandé que les policiers reçoivent une meilleure formation à la désescalade et aux communications avec les personnes présentant des troubles affectifs.

59 En février 2008, la Police de Toronto a reçu un appel au sujet de M. Debassige, 28 ans, qui avait volé des citrons chez un dépanneur. M. Debassige était armé d’un couteau de trois pouces. Quand la police s’est approchée vers lui, il a brandi son couteau. Les policiers lui ont ordonné de le poser et de ne plus bouger, l’avertissant qu’ils feraient feu s’il n'obéissait pas à cet ordre. Mais il a continué d’avancer vers les policiers, qui lui ont tiré cinq fois dans la poitrine, à une distance de six pieds.

60 M. Debassige avait un long passé de violence et souffrait depuis longtemps de psychose, d’abus d’alcool et du syndrome d’alcoolisme fœtal. L’Unité des enquêtes spéciales n’a porté aucune accusation. Le jury du coroner a recommandé une meilleure collecte et un meilleur partage des données sur les personnes atteintes de troubles mentaux qui ont affaire au système de justice.

61 La Police provinciale de l’Ontario (OPP) a été appelée à une résidence à Huronia West, que partageaient M. Minty, 59 ans, et sa mère. L’incident a eu lieu le 22 juin 2009, et la police est intervenue à la suite d’une plainte disant que cet homme atteint de déficience mentale avait essayé de frapper un vendeur qui faisait du porte-à-porte. Quand M. Minty, tenant un petit couteau de poche, s’est avancé vers le policier de l’OPP, celui-ci a tiré cinq fois sur lui, le tuant par balles.

62 Une semaine plus tard, M. Schaeffer, 30 ans, souffrant de troubles schizo-affectifs, d’attaques de panique et de troubles de la personnalité, a été abattu par un policier de l’OPP près de Pickle Lake. Lui et un collègue enquêtaient alors sur un bateau disparu et ils ont allégué que M. Schaeffer – qui était seul avec eux sur les lieux – les avait menacés avec un couteau et du répulsif à ours.

63 Dans ces deux cas, l’Unité des enquêtes spéciales a déterminé qu’aucune accusation ne devrait être portée, mais elle a exprimé ses inquiétudes quant aux méthodes suivies par les policiers pour rédiger leurs notes. En effet, dans les deux cas, il avait été conseillé à ceux-ci de consulter un avocat avant de rédiger leurs notes, ce qui avait eu des effets sur l’indépendance et la spontanéité de ces notes. Les familles Schaeffer et Minty ont fait appel avec succès jusqu’à la Cour suprême du Canada. En 2013, cette Cour a déclaré que les policiers devraient rédiger leurs notes immédiatement après un incident, sans l'aide d’avocats qui les vérifient ou contribuent à leur rédaction avant leur remise à l’UES.

64 En mars 2011, le jury du coroner dans l’affaire Schaeffer a recommandé que des améliorations soient apportées aux politiques de communication pour les policiers en régions éloignées, ainsi qu'à la formation aux interactions avec les personnes ayant des problèmes de santé mentale. En juin 2014, le jury du coroner dans l’affaire Minty a recommandé que les policiers et les répartiteurs d’appels de l’OPP soient mieux formés, pour pouvoir mieux comprendre les personnes atteintes de maladie mentale, de déficience de développement ou de troubles affectifs.

65 Le 24 juin 2010, l’OPP a répondu à une plainte concernant une agression dans une résidence de Collingwood. M. Firman, 27 ans, atteint de schizophrénie, est devenu agité quand les policiers ont essayé de l’arrêter. Il a donné un coup de coude à un agent de police, au visage, et a continué d’avancer. La police l'a alors frappé au Taser. Puis il a été transporté à l’hôpital, où son décès a été constaté. L’UES n’a porté aucune accusation.

66 Lors de l’enquête du coroner, des témoignages contradictoires ont été déposés sur la cause du décès, mais le pathologiste principal de l’Ontario a certifié que le Taser avait été un facteur clé dans la mort de M. Firman, décédé d’une arythmie du cœur. Environ la moitié des recommandations du jury portaient sur l’usage des Tasers; les autres préconisaient de donner une meilleure formation aux policiers pour qu'ils reconnaissent les comportements liés aux maladies mentales et y réagissent en conséquence.

67 M. Jones avait tout juste 18 ans en août 2010, mais il connaissait déjà des problèmes de dépression, d’alcool et de drogues. Étant rentré chez lui après avoir bu avec un ami, il s’est mis à crier et à tout chambouler. Sa mère a alors appelé la police de Brantford. Quand les policiers sont arrivés, M. Jones était debout sur le perron, tenant deux grands couteaux, dont il a posé les lames sur sa gorge. Il a demandé aux policiers de le tuer.

68 Les policiers l’ont suivi alors qu’il rentrait dans la maison, mais là, il a lancé l’un des couteaux vers eux. Une pulvérisation de gaz poivré n’a pas réussi à l’arrêter. Quand il a levé un couperet au-dessus de sa tête, les policiers ont tiré sur lui à quatre reprises et l'ont tué.

69 En mai 2012, le jury du coroner a fait 26 recommandations, préconisant entre autres que les policiers de première ligne reçoivent « une formation actualisée obligatoire » sur les problèmes des personnes atteintes de maladie mentale. Il a aussi demandé que le Ministère revoie la formation donnée au Collège de police de l’Ontario sur les interactions entre les policiers et les personnes atteintes de maladie mentale, de même que le modèle d’usage de la force en vigueur en Ontario, les normes de communication tactique et l’emploi de la sommation par la police. Il a aussi proposé de déployer plus d'équipes mobiles d’intervention en situation de crise qui regrouperaient à la fois des professionnels de la santé mentale et des policiers.

70 À la fin de l'enquête de l’UES en 2011, aucune accusation n'a été portée. Mais, fait rare, l’enquête a été rouverte en janvier 2015 pour cause de preuve « manifestement nouvelle ». Alors que nous rédigions ce rapport, il n’y avait eu aucune autre évolution.

71 M. Mesic, 45 ans, patient volontaire du service psychiatrique de St. Joseph’s Healthcare à Hamilton, atteint d’anxiété et de dépression, est sorti de cet établissement à sa demande en juin 2013. Peu après, la police a répondu à un appel disant qu’il avait marché en plein devant un autobus et qu’il errait au milieu de la circulation sur la grand-route, près de chez lui.

72 Les policiers ont ordonné à M. Mesic de quitter la route, et il a commencé à grimper un remblai en direction de sa maison. Ils l’ont retrouvé dans sa cour arrière, où ils ont tiré sur lui et l’ont tué. Lors de son décès, sa fiancée était enceinte.

73 L’UES n’a porté aucune accusation. L’une des recommandations du jury dans l’enquête de 2014 était que les policiers reçoivent une formation annuelle donnée par « des clients / des survivants de services de santé mentale ».

74 M. Eligon, 29 ans, père d’un fils, était dans un hôpital de Toronto en vertu de la Loi sur la santé mentale en février 2012, mais il s’en est échappé. Il est allé chez un dépanneur, où il a pris deux paires de ciseaux et a infligé des coupures au propriétaire du magasin, qui a appelé le 911. Quand la police est arrivée, elle a trouvé M. Eligon dans la rue, en tenue d’hôpital et en chaussettes, brandissant les ciseaux.

75 Sept policiers lui ont fait face, pistolets dégainés, et ont lancé leur sommation habituelle, mais il a continué d’avancer. Ils ont tiré sur lui, et il est décédé à l’hôpital où il avait été transporté. L’UES n’a pas porté d’accusations, mais son directeur de l’époque (Ian Scott) a déclaré que ce décès soulevait des questions quant à la formation donnée aux policiers pour les préparer à traiter avec des personnes atteintes de maladie mentale et au bien-fondé de la fourniture éventuelle de Tasers aux policiers de première ligne.

76 L’enquête du coroner en 2014 sur le décès de M. Eligon s’est aussi penchée sur la mort de Sylvia Klibingaitis, 52 ans (tuée en octobre 2011) et de Reyal Jardine-Douglas, 25 ans (tué en août 2010). Ces trois personnes avaient toutes des problèmes de santé mentale et toutes trois tenaient des armes blanches quand elles ont été tuées par des policiers de Toronto. Dans aucun des trois cas, l’UES n’a porté d’accusations. En revanche, les recommandations du jury du coroner sont les plus complètes et les plus approfondies faites jusqu’à présent sur la formation des policiers en matière de désescalade.

77 En septembre 2015, le Service de police de Toronto a répondu en détail aux 74 recommandations du jury, précisant que 85 % d’entre elles avaient déjà été complètement mises en œuvre[21]. Celles-ci étaient notamment les suivantes :

-

Former les policiers à déterminer si une personne est en crise et à tenir compte de tous les renseignements pertinents sur son état, pas seulement de son comportement, lorsque la situation s'y prête et ne met aucunement en danger les policiers et le public.

-

Former les policiers, dans toute la mesure du possible et conformément aux règles de sécurité pour eux-mêmes et pour le public, à offrir verbalement leur aide et leur sollicitude quand ils se trouvent face à une personne en crise, avec une arme blanche.

-

Mettre au maximum l’accent sur les techniques verbales de désescalade dans tous les aspects de la formation annuelle donnée en cours d’emploi au Toronto Police College.

-

Intégrer des scénarios plus dynamiques (p. ex., incluant des badauds, de la circulation et des distractions) et des exemples tirés d’incidents de la vie réelle à la formation au recours à la force.

78 Les familles qui ont parlé à nos enquêteurs et les jurys qui ont délibéré lors de très nombreuses enquêtes du coroner ont toutes et tous été aux prises inlassablement avec ces mêmes questions fondamentales : Comment ceci peut-il se produire? Comment un policier qui répond à un appel à propos d’une personne en détresse finit-il par la tuer?

79 Le Code criminel du Canada permet aux policiers de recourir à la force pour empêcher la perpétration de certaines infractions. Un policier peut uniquement employer la force nécessaire pour cette fin et il doit agir en s’appuyant sur des motifs raisonnables[22]. L’article 25 du Code justifie l'usage d'une force qui cause la mort ou des lésions corporelles graves dans certaines circonstances, par exemple pour protéger la vie du policier ou celle de toute autre personne[23].

80 Les services de police ont adopté des modèles d’« usage de la force » pour représenter les facteurs dont les policiers doivent tenir compte dans des situations qui peuvent mener à la violence. Ces modèles donnent un aperçu des raisons pour lesquelles les policiers agissent comme ils le font dans certaines situations. Notre enquête a examiné des modèles utilisés de par le passé et actuellement, en Ontario et ailleurs, en raison des répercussions qu’ils ont sur la formation, les politiques et les procédures, et en fin de compte sur la culture au sein de la police.

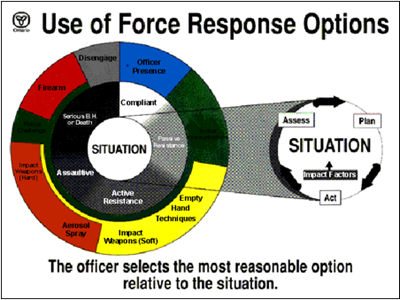

81 Certains corps de police au Canada ont commencé à adopter des modèles d’usage de la force dans les années 1980, mais ce n’est qu’en 1993 que l’Ontario en a conçu un[24]. Le modèle de l'Ontario visait à tenter de garantir qu'une formation axée sur les questions actuelles de recours à la force était fournie aux recrues et aux policiers en exercice[25]. Le modèle se présentait alors, tout comme aujourd’hui, sous forme d'un graphique en forme de roue qui représentait les différents éléments du processus d’évaluation et de réaction d’un policier face à une situation. (Voir Figure 1)

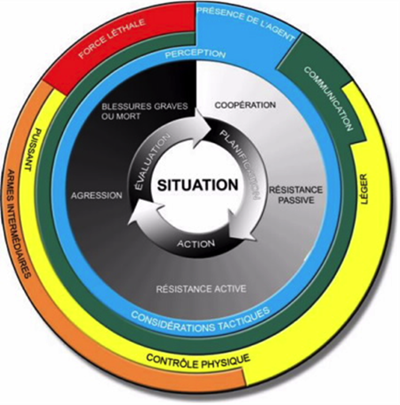

82 En 1999, l’Association canadienne des chefs de police (ACCP) a appuyé un projet visant à concevoir un modèle national, appelé Cadre national de l’emploi de la force. Quelque 65 spécialistes du Canada et des États-Unis se sont réunis au Collège de police de l’Ontario pour élaborer ce cadre[26].

83 L’un de leurs critères était que le Cadre national ne laisse pas présumer une progression linéaire des options d’usage de la force. De plus, ils ont souligné que le modèle devrait être facile à comprendre – pas seulement par les policiers, mais aussi par le public. Comme l’indiquent les documents de formation du Collège de police de l’Ontario que nous avons examinés, ce modèle « aide les policiers et le public à comprendre pourquoi et comment un policier peut réagir en employant la force »[27].

84 Le Cadre national n’a pas pour but de dicter des politiques à un organisme policier, de prescrire des réponses précises à des situations, ou de justifier l’usage de la force par un policier[28]. Le coordonnateur des questions de santé mentale au Collège de police de l’Ontario a ainsi expliqué l’objectif à nos enquêteurs :

Les recrues nous posaient ces questions : « Bon, alors si quelqu’un vient vers moi avec un bâton de baseball, je peux sortir mon arme à feu, c'est ça? Et tirer sur lui? Et si on en arrivait à ça, mon acte serait justifié, oui? » En fait, ce n’est pas si simple… Ce n’est pas simplement une question de lui avec ce couteau et de moi avec mon pistolet… [Le policier] doit penser à tous les autres facteurs qui entrent en jeu.

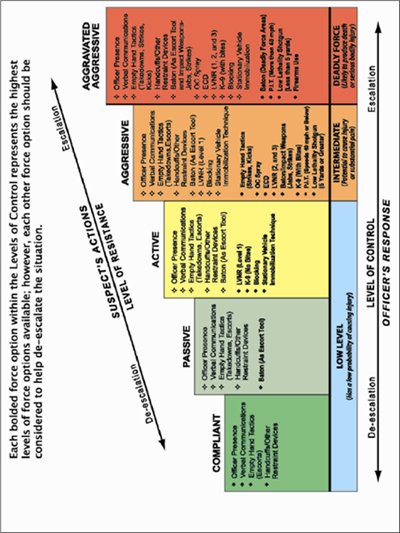

85 Dans cet objectif, le modèle du Cadre national enseigne aux policiers à évaluer en continu la situation et le comportement d’un sujet, et à sélectionner l’option la plus raisonnable compte tenu des circonstances alors perçues. Les « options d’usage de la force » sont indiquées sur la roue et elles se chevauchent pour montrer que le policier peut en utiliser une seule, ou plusieurs à la fois. Le modèle tient compte du fait que, dans des situations tendues, le comportement du sujet et les perceptions du policier, de même que les considérations tactiques, peuvent changer à tout moment. (Voir Figure 2)

86 Les options d’usage de la force sont les suivantes :

-

Présence du policier : Ceci fait simplement référence au fait que la police est sur les lieux; ce n’est pas strictement une option d’usage de la force.

-

Communications : Communications verbales et non verbales pour maîtriser ou régler la situation.

-

Techniques de maîtrise physique/à mains nues : Ces options ne font appel à aucune arme, mais vont de techniques « douces » (immobiliser un sujet) à des techniques « dures » comme les coups de poing ou de pied.

-

Armes intermédiaires : Ce sont des armes de police non mortelles, qui n’ont pas pour but de causer la mort ou de graves blessures corporelles, comme les matraques, les Tasers ou les pulvérisateurs d'O/C.

-

Force mortelle : C'est le déploiement du plus grand niveau de force, et ceci veut généralement dire que le policier se sert de son arme à feu, mais fait référence à toute arme ou technique qui vise à causer, ou va probablement entraîner, de graves blessures corporelles ou la mort.

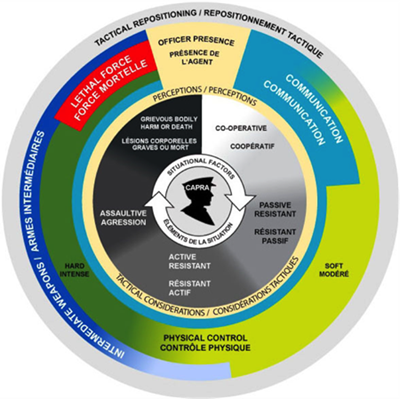

87 En 2004, l’Ontario a élaboré son modèle actuel d’usage de la force à partir du Cadre national conçu en 1999. Ce modèle a été approuvé par le ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels, après vérification et approbation par son Comité consultatif des services policiers[29]. L’article 5 des lignes directrices du Ministère sur l’usage de la force dans le Manuel des normes policières, en vertu de la Loi sur les services policiers, stipule que les chefs de police « doivent » s'assurer que la formation à l’usage de la force donnée à leurs membres s'inscrit « dans le cadre » de ce modèle.

88 Tout comme le Cadre national de l’emploi de la force, la version ontarienne de ce modèle se présente sous la forme d’une roue, montrant l'intensification des options de recours à la force, dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre. Dans chacun des deux cas, les « communications » sont incluses et présentées sous forme d’un cercle qui entoure toutes les options d’usage de la force, soulignant que les techniques de communication peuvent être utilisées à tout moment. (Voir Figure 3)

89 Aucun des deux modèles ne fait précisément référence à la désescalade. Certes, beaucoup de personnes que nous avons interviewées comprenaient que celle-ci faisait partie de l’option des « communications », mais les opinions divergeaient quant à la signification de ces deux termes. Un instructeur du Collège de police de l’Ontario nous a dit que la désescalade sous-tend chaque aspect d’une décision menant à l’usage de la force :

En fin de compte, même quand [la police] a recours à la force, elle doit percevoir quand celle-ci est suffisante pour désamorcer la situation. Tout aspect des services policiers, où on envisage l’application de la force, ou l’usage de la force, a pour fondement la désescalade.

90 Un autre instructeur de ce Collège a défini la désescalade un peu différemment. Voici ce qu’il a expliqué à nos enquêteurs :

Quel est le but ultime dans chaque situation? Désamorcer la situation et la régler. Autrement, elle durerait encore. Alors dans chaque situation que vit un policier, à un moment donné, il faut en arriver à une fin.

Quand nous lui avons demandé si cela voulait dire que le recours à une force mortelle pouvait être considéré comme une forme de désescalade, il a répondu : « Eh bien, oui. Si quelqu’un montre ce type de comportement, alors ce serait la résolution finale. »

91 En juillet 2013, peu après le décès de Sammy Yatim, le chef du Service de police de Toronto, Bill Blair, a demandé à Frank Iacobucci, juge en chef de la Cour suprême alors à la retraite, d’effectuer un examen indépendant de l’usage de la force mortelle au sein de ce service. Le rapport, intitulé Police Encounters With People in Crisis, est paru en juillet 2014. Il a fait 84 recommandations dans le but ambitieux, mais louable, que l’usage de la force par les policiers ne cause plus jamais de morts[30]. En septembre 2015, la Police de Toronto a fait savoir[31] que 79 des recommandations (94 %) étaient au moins partiellement mises en œuvre, tandis que 67 (80 %) l’étaient complètement.

92 Les recommandations du juge Iacobucci sont adressées au Service de police de Toronto, et non au Ministère, mais son rapport expose des problèmes et propose des solutions logiques qui s’appliquent à l’ensemble de la province et méritent de retenir l’attention du Ministère. Le juge a notamment fait remarquer que le modèle de « la roue » de l’usage de la force en Ontario « n’est pas une aide visuelle particulièrement efficace ou intuitive ». Il a souligné que, bien que ce modèle encourage une évaluation continue d’une situation, « étonnamment, peu d'importance est accordée à la nécessité de tenter d’utiliser divers moyens de communication avant d’employer la force ou une arme face à une personne ». Il a aussi précisé que les lignes directrices sur l’usage de la force en Ontario, fondées sur le modèle, « ne soulignent pas que les techniques de communication et de désescalade doivent impérativement faire partie de toutes les étapes de la réaction des policiers aux situations de crise »[32].

93 M. Gary Ellis, ancien surintendant des Services de police de Toronto, et actuellement chef de programme des études de la justice à l’Université de Guelph-Humber, a dit à nos enquêteurs que le modèle d’usage de la force de l’Ontario est utile mais problématique car il ne fait pas référence aux techniques de désescalade comme le désengagement et le confinement. Il serait possible d’améliorer ce modèle par des références aux techniques de désescalade, a-t-il dit.

94 Les techniques de désescalade sont enseignées lors de la formation à l’usage de la force pour les policiers, a dit M. Ellis, mais à son avis, elles ne sont peut-être pas soulignées comme elles le devraient. Il a souligné que conformément aux lignes directrices sur l’usage de la force énoncées par le Ministère, la formation des policiers doit s'inscrire dans le cadre du modèle d’usage de la force et qu’à présent, « il n’y a rien » dans ce modèle pour indiquer que les policiers devraient être formés à la désescalade.

Figure 1 – Modèle d’usage de la force, Ontario, 1993

Figure 2 – Cadre national de l’emploi de la force

Modèle de recours à la force de l’Ontario

L’agent évalue continuellement la situation et opte pour la forme de recours à la force la plus raisonnable compte tenu des circonstances perçues au moment de la situation.

Figure 3 – Modèle actuel, Ontario

95 Alors que les techniques policières ont évolué au fil du temps, les modèles de « roue » et même l’expression « usage de la force » en sont venus à susciter des critiques. Certaines des personnes que nous avons interviewées considéraient que les modèles canadiens et ontariens devraient éliminer le terme de « force ». Nous avons trouvé un document d’un service de police municipale de l’Ontario qui demandait au ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels de remplacer le nom de ce modèle par « Modèle d’intervention de la police ».

96 Mme Frum Himelfarb, ancienne commissaire adjointe intérimaire à la Gendarmerie royale du Canada, a contribué à l’élaboration du Modèle d’intervention pour la gestion d’incidents, utilisé par ce service. (Voir Figure 4) Elle a dit à nos enquêteurs que la terminologie d'un modèle de gestion de situation envoie au public et aux policiers un message disant que « nous sommes ici dans l’intérêt de la sécurité du public; l’objectif est de trouver le moyen d’intervention approprié le moins perturbant, le moins risqué dans les circonstances données ». Elle a ajouté qu’un tel modèle encourage la réalisation d’actions propices à désamorcer le risque de violence, tout en admettant que ceci n’est pas toujours possible.

97 Le modèle de la GRC se présente lui aussi sous forme de roue, mais avec une différence importante : il inclut un « repositionnement tactique » dans un anneau extérieur, soulignant que les options autres que l’usage de la force peuvent être utilisées à tout moment pour désamorcer une situation – par exemple en mettant à la fois du temps et de la distance entre le sujet et les policiers, soit « un désengagement ».

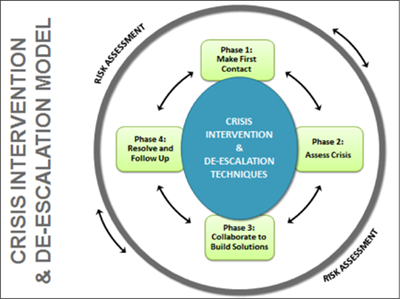

98 La Police de l’État de Victoria en Australie utilise elle aussi une roue pour son « Modèle d’options tactiques », décrit comme une aide visuelle conçue pour aider les policiers à déterminer l’option tactique la plus pertinente ou des solutions autres que l’usage de la force. Les tactiques possibles sont représentées par des secteurs séparés du diagramme – incluant la « négociation » et le « désengagement tactique » – tandis que les « communications » constituent un anneau séparé qui entoure le tout. (Voir Figure 5)

99 Le Modèle d’options tactiques a été instauré lors d’un examen complet de la formation, des politiques et des tactiques de sécurité opérationnelle de ce service de police. Plutôt que d’adopter un modèle de « continuum » d’usage de la force, ce service a sélectionné ce modèle après avoir constaté que, dans le cas d'un tel continuum, le choix de l'option de recours à la force et de l’équipement doit toujours être supérieur d’un cran à la menace présentée par le sujet – c’est ce qu'on appelle la « théorie du plus un ». Le résultat est le suivant : « Alors que la désescalade reste l’objectif, le concept du continuum mène à la perception psychologique d’une escalade »[33].

100 La Colombie-Britannique a créé un modèle spécialement conçu pour les cas d’interaction avec des personnes présentant des troubles affectifs – mais qui peut être employé dans toute situation qui justifie une désescalade. Ce modèle a été élaboré dans le sillage du rapport d’enquête du juge Thomas Braidwood en 2009 sur la mort de Robert Dziekanski, décédé à la suite d’une décharge de Taser infligée par un policier. Ce rapport a recommandé à la province d’exiger que tous les policiers reçoivent une formation sur « l'intervention et la désescalade en situation de crise » (IDC).

101 Ce modèle est le fondement de la formation. L’objectif principal du modèle IDC est que le policier établisse un rapport avec le sujet et contribue à désamorcer la situation pour faciliter la communication et trouver une solution. Bien que représenté par une « roue », il se caractérise par des flèches bidirectionnelles représentant le flux naturel des communications en situation de crise – et soulignant qu’un policier doit sans cesse évaluer les risques à mesure que l'incident évolue. (Voir Figure 6)

102 En 2012, le Service de la police métropolitaine de Las Vegas a remplacé sa « roue » d’usage de la force par un modèle à échelle progressive qui reflète l’importance accrue attachée à la désescalade. Ce modèle reconnaît que les policiers peuvent toujours choisir de désamorcer une situation en fonction des circonstances ou des possibilités. Il constitue une réponse à la critique principale faite à propos des modèles de « roue » unidirectionnelle ou de continuum d'usage de la force, disant qu'ils représentent uniquement une situation en escalade, sans suffisamment montrer qu’il est aussi possible d’opter pour la désescalade[34]. (Voir Figure 7)

103 Le modèle de Las Vegas est appuyé par une politique d’usage de la force qui définit les tactiques de désescalade et qui souligne clairement qu’elles doivent être envisagées et utilisées par les policiers dans les situations de violence potentielle pour les contrôler sans recourir à la force. Les tactiques suggérées sont entre autres les suivantes : se retirer vers une position plus sûre, mettre de la distance entre le policier et le sujet, recourir à la persuasion verbale et tenter de ralentir le rythme d’évolution de la situation. Ceci vient donner réponse aux problèmes soulevés lors de fusillades impliquant les policiers de Las Vegas, où il avait été conclu que « ne pas désamorcer la situation et ne pas ralentir le rythme d’évolution de l’incident était l’une des erreurs tactiques les plus courantes »[35].

104 Certains des instructeurs du Collège de police de l’Ontario que nous avons interviewés attachaient peu d'importance au concept et au contenu des modèles utilisés, disant que ce n'étaient que des aides pédagogiques. Selon eux, il est bien plus essentiel de veiller à ce que les policiers soient formés aux tactiques de désescalade et qu'ils s'y exercent lors de scénarios durant la formation. Comme l’un deux l’a expliqué :

Durant un incident critique, absolument personne ne pense [au modèle d’usage de la force]. La représentation que vous faites du modèle ne va donc pas influer sur ce que les gens vont faire quand ils pensent que leur vie, ou celle de quelqu’un d’autre, se trouve en danger.

105 Quoi qu’il en soit, c’est au ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels qu’appartient la responsabilité première du modèle d’usage de la force et de la formation de la police. Tout changement – au modèle, à la façon dont les policiers sont formés à l’utiliser, ou à la culture du milieu policier en général – doit commencer par lui.

106 Pour comprendre où en est la formation à la désescalade en Ontario, et comment il est possible de l’améliorer, il est essentiel d’étudier en détail le rôle du Ministère dans le concept et la prestation de cette formation – ainsi que le leadership dont il a fait preuve – ou non – à cet égard.

Figure 4 – Modèle de la GRC

Figure 5 – Modèle de la Police de l’État de Victoria (Australie)

Figure 6 – Modèle d’intervention et de désescalade en situation de crise en Colombie-Britannique

Figure 7 – Modèle du Service de la police métropolitaine de Las Vegas

107 En Ontario, le maintien de l’ordre est assuré par les services de police municipale/régionale ainsi que par la Police provinciale de l’Ontario, qui relèvent tous de la responsabilité du gouvernement de l’Ontario, et plus précisément du ministère de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels.

108 Les devoirs et les pouvoirs du Ministère sur le plan du maintien de l’ordre sont définis par la Loi sur les services policiers. Cette Loi autorise entre autres le Ministère à :

-

Élaborer des programmes visant à accroître le caractère professionnel de la formation, des normes et des pratiques policières, et en faire la promotion.

-

Élaborer, appliquer et gérer des programmes, créer, tenir et administrer des dossiers statistiques et effectuer des recherches en ce qui concerne les services policiers et les questions connexes.

-

Donner des directives et des lignes directrices concernant les politiques[36].

109 Cette Loi permet aussi au lieutenant-gouverneur en conseil d'édicter des Règlements qui prescrivent les normes régissant les services policiers, de réglementer l’usage de la force par les membres des corps de police, et de prescrire des cours de formation pour les membres des corps de police ainsi que les normes à cet égard[37].

110 Le budget total du Ministère se chiffre à 2,3 milliards $. Le Ministère a la responsabilité de la Police provinciale de l’Ontario, qui est le plus grand corps de police de la province, avec un budget de 1 milliard $ l’an dernier. Le Ministère consacre environ 255 millions $ à la sécurité publique, ce qui inclut le fonctionnement du Collège de police de l’Ontario, et 130 millions $ à l'administration.

111 Quiconque souhaite devenir policier municipal ou provincial en Ontario doit suivre la formation de base des agents de police au Collège de police de l’Ontario, qui relève de la Division de la formation en matière de sécurité publique du Ministère. Chaque recrue dans la province commence donc par la même formation de base. Mais ensuite, les 52 services de police municipale et la Police provinciale de l’Ontario disposent d'une grande latitude en ce qui concerne la formation de leurs membres.

112 La Division de la sécurité publique du Ministère, qui était précédemment responsable du Collège de police de l’Ontario, est chargée de contrôler et d’inspecter les services policiers. Elle a élaboré un Manuel des normes policières qui énonce des lignes directrices pour aider les commissions de services policiers, les chefs de police, les associations de police et les municipalités à mieux comprendre et appliquer la Loi sur les services policiers et ses Règlements[38].

113 Parmi les lignes directrices les plus importantes du manuel figurent celles sur l'usage de la force. Leur but est d'aider les chefs de police et les commissions de services policiers à respecter les exigences du Règlement sur le matériel et l’usage de la force, en vertu duquel tous les chefs de police doivent notamment veiller à ce que les membres de leur service achèvent avec succès des cours de formation sur l’usage de la force et des armes à feu une fois par an. Le Règlement stipule que ces cours doivent comprendre une formation sur les questions suivantes : 1) exigences légales; 2) usage du jugement; 3) sécurité; 4) théories relatives à l’usage de la force; et 5) habileté pratique[39].

114 La terminologie utilisée par le Ministère dans les lignes directrices sur l’usage de la force varie en anglais selon le contexte, les mots « shall » et « should » faisant une distinction entre les éléments obligatoires et les éléments laissés à la discrétion du service de police. [La version française de ce texte de loi utilise uniquement « doit » pour ces deux mots.]

115 Par exemple, les lignes directrices indiquent que chaque chef de police doit [shall] s'assurer que les membres de son service suivent une formation sur l’usage de la force et des armes à feu une fois par an, et que cette formation doit [shall] comprendre les cinq éléments au sujet des armes à feu et du recours à la force indiqués dans le Règlement sur le matériel et l’usage de la force mentionné ci-dessus[40]. Mais elles indiquent ensuite que chaque chef de police doit [should] s’assurer que le cours de formation sur l’usage de la force « s’inscrit dans le cadre du modèle d’usage de la force utilisé en Ontario » et qu’il est également « conforme aux options approuvées par le Ministère en matière d’usage de la force », c’est-à-dire la présence d’un agent, la communication, le contrôle physique, les armes intermédiaires et la force mortelle[41]. En d’autres termes, la formation des policiers à l’usage de la force et des armes à feu est obligatoire, mais une certaine discrétion est laissée aux services de police quant à la forme qu'elle doit prendre.

116 Nos enquêteurs ont été informés par les instructeurs du Collège de police de l’Ontario et des fonctionnaires ministériels qu’une telle latitude est laissée aux services de police quant au concept et à la prestation de la formation, car ceux-ci ont besoin d’une certaine souplesse pour tenir compte des circonstances locales. Voici ce qu’un instructeur nous a déclaré :

En fonction du lieu où vous travaillez, vous allez peut-être vous trouver confronté à des éléments différents en tant que policiers, selon que vous êtes en milieu rural ou que vous travaillez en milieu urbain. À mon avis, le Ministère ne devrait pas se trouver dans une position où il dicte à chaque service de police : « C'est ce que vous allez faire. »

117 En revanche, un autre instructeur était d’avis différent :

Je crois qu’il serait utile en tant que province d’avoir une base établie par le Ministère et fondamentalement, il s'agit d’uniformiser l’application de l’usage de la force et la manière dont les gens s’attendent à être traités. Le fondement devrait être le même aussi bien dans le Nord de l’Ontario qu’à Toronto. Je pense qu’il devrait revenir à chacun des services de concevoir une formation dont le contexte est plus adapté à sa communauté, mais je crois qu'il serait bon que la structure générale vienne du Ministère.

118 Plusieurs instructeurs ont dit à nos enquêteurs qu’ils avaient l’impression que la formation donnée par la plupart des services de police sur l’usage de la force et des armes à feu correspondait au cours de formation de base des agents de police offert au Collège de police de l’Ontario – et était donc conforme aux lignes directrices en vigueur dans la province. Malheureusement, ceci est impossible à vérifier, car le Ministère ne conserve aucune donnée sur le contenu de la formation donnée par chacun des services de police, ni même sur le nombre d’heures qui y sont consacrées.

119 En général, les fonctionnaires du Ministère, de même que les instructeurs du Collège, se sont déclarés en faveur des appels lancés pour une formation plus poussée des policiers à la désescalade. Cependant, nos enquêteurs ont aussi découvert un certain scepticisme. Par exemple, lors d’un échange écrit avec le Ministère sur les interactions de la police avec les personnes atteintes de maladie mentale, le coordonnateur des questions de santé mentale du Collège a souligné qu’un renforcement de la formation « n’était peut-être pas une panacée aussi extraordinaire que beaucoup le pensent ». Dans sa réponse, il a cité le manque d’études empiriques sur la formation que les policiers devraient recevoir et a exprimé le doute qu'un tel renforcement mène à de meilleurs résultats sur le plan des interactions avec les personnes en crise.

120 La Loi sur les services policiers accorde au Ministère le droit de définir des normes pour les services policiers et ce, pour une bonne raison. Comme l’un des fonctionnaires du Ministère l’a dit lors d’une entrevue avec nos enquêteurs, ceci garantit que « peu importe où vous vous trouvez dans la province de l’Ontario, en tant que citoyen, vous allez obtenir le même niveau de service de la police ».

121 Le Ministère a une longue tradition d'adoption de normes dans l’intérêt du public. L’exemple le plus clair est le Règlement Adequacy and Effectiveness of Police Services[42], qui définit les procédures et les politiques pour des choses fondamentales comme les enquêtes criminelles. Le fonctionnaire ministériel nous a expliqué que de telles questions exigent « un niveau d’uniformisation dans toute la province » et que « le seul moyen d’y parvenir vraiment est d’imposer des normes ».

122 Les lignes directrices sur l’usage de la force en vigueur actuellement dans cette province résultent du fait qu’en 1992, le gouvernement a senti le besoin d’effectuer une certaine uniformisation de la formation à l’usage de la force. Depuis, seules des modifications mineures y ont été apportées, en dépit des changements dans les techniques policières et des centaines de recommandations d’enquêtes du coroner.

123 Mais en 1999, après une série de poursuites policières à grande vitesse ayant entraîné des décès et des blessures chez plusieurs civils, le Ministère s'est prévalu de son droit d'édicter des normes. Des lignes directrices sur les poursuites policières étaient en place depuis les années 1980, mais les pratiques variaient un peu partout dans la province, et les protestations du public se faisaient plus vives en raison du nombre de passants innocents qui étaient tués lors de crimes relativement mineurs. Lors de son entrevue avec nos enquêteurs, l’ancien commissaire de la Sécurité communautaire au Ministère s’est souvenu que ces événements « avaient incité le gouvernement à dire “vous savez, on doit changer le comportement des policiers” ». De là est né le Règlement Suspect Apprehension Pursuits sur les poursuites visant l’appréhension de suspects, en vertu de la Loi[43].

124 Bien que n'ayant pas contribué à la mise en place de ce Règlement, l’ancien sous-ministre adjoint de la Division de la sécurité publique à qui nos enquêteurs ont parlé a souligné qu’il y avait de nombreux exemples où la province applique des normes dans « l’intérêt provincial ». Comme il l’a dit :

À un moment donné, c’est clair… une forme courante, une cohérence, devient nécessaire. Le gouvernement doit intervenir et s'assurer que les pratiques exemplaires… sont utilisées par tous.

125 Un exemple plus récent est celui des vérifications ciblées, ou « fichage ». En juin 2015, alors que le public s’inquiétait profondément des répercussions disproportionnées de ce processus sur les minorités visibles, le Ministère a annoncé qu’il allait élaborer un nouveau Règlement à cet égard. À la suite de consultations publiques, une ébauche du Règlement a vu le jour en octobre 2015, et la touche finale y a été apportée en mars 2016. Le Règlement entrera en vigueur le 1er janvier 2017 et la nouvelle formation qui s'y rattache sera mise en œuvre dans tous les services de police au printemps, à l’été et à l’automne[44].

126 Indéniablement, les services locaux de police auront besoin d’une certaine souplesse pour adapter les aspects de cette formation à la désescalade des situations conflictuelles propres à leurs communautés. Mais certains croient que la trop grande latitude laissée aux services de police a mené à l'apparition d’un système disparate, où la formation donnée aux policiers dans une partie de la province diffère de celle offerte ailleurs.

127 Le Ministère a montré que, face à certains problèmes, il est dans l’intérêt du public de garantir la cohérence d'un processus à l’échelle provinciale, et il a pris des mesures en ce sens. Mais jusqu’à présent, tel n’a pas été le cas pour la formation à la désescalade. Nonobstant les lignes directrices ministérielles, la mesure dans laquelle elles sont respectées, voire le type de formation à la désescalade offert aux policiers, reste discrétionnaire. Il revient à chacun des services de police d'en décider.

128 À la suite du décès de Robert Dziekanski, tué par quatre policiers de la Gendarmerie royale du Canada armés de Tasers, à l’Aéroport international de Vancouver en 2007, une enquête dirigée par le juge Thomas Braidwood a recommandé que tous les policiers de la province soient formés aux techniques d’intervention et de désescalade en situation de crise (IDC)[45].

129 En réponse au rapport du juge Braidwood paru en 2009, la province a établi une Norme de formation à l’intervention et à la désescalade en situation de crise[46], stipulant que tous les policiers de première ligne, les superviseurs et les recrues doivent suivre une formation en IDC approuvée par la province[47]. Cette formation comprend un cours en ligne d’une durée de trois à quatre heures, plus sept heures d’enseignement en classe. Tous les policiers doivent refaire le cours en ligne tous les trois ans, pour une remise à niveau de leurs compétences.

130 La Colombie-Britannique est la seule instance canadienne où une telle norme existe. L’élaboration du cours résulte d’une concertation entre des spécialistes du secteur policier et d'autres secteurs, mais le ministère de la Justice et le Solliciteur général ont joué le rôle principal sur le plan de la coordination.

131 Plusieurs fonctionnaires ministériels ont dit à nos enquêteurs qu’il n’était nullement prévu de mettre en place des lignes directrices, des directives ou des Règlements sur la désescalade. Cependant, le 27 août 2013, soit exactement un mois après le décès de Sammy Yatim, la ministre de la Sécurité communautaire et des Services correctionnels a apporté un changement important à la réglementation de l’usage de la force. Mme Madeleine Meilleur, alors ministre, a annoncé que les services de police pourraient permettre à tous les policiers d’utiliser des Tasers, au lieu de restreindre leur utilisation aux superviseurs de première ligne et aux membres d’équipes spécialisées.